Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

How The Gay Activist Alliance Mainstreamed LGBTQ Rights In The Years After The Stonewall Uprising

In the years after the Stonewall Uprising, the real fight for LGBTQ liberation was fought tooth and nail by an offshoot group that managed to effect major change for marginalized Americans.

Every month in the mid-1960s in New York City, hundreds of consenting adults would be arrested in police entrapment stings for a crime that authorities had named “homosexual solicitation.” Shunned from most bars and public establishments, they were left to cruise for connections, sexual or otherwise, in the city's parks and public spaces. These arrests, designed to humiliate, marginalize, and destroy the lives of some of the city’s most vulnerable residents, stemmed from a 1920s law that named homosexual acts “degenerate disorderly conduct.”

This was just one tactic used in mid-century America that shamed the country's millions of LGBTQ people over their identity. For the massive amount of New Yorkers arrested under the law before 1966, when such use of entrapment was drawn down by the NYPD under mounting outside pressure, this frequent fear of arrest, then losing one’s job, and finally being shunned from everyday life, was deeply palpable. This is a taste of the stakes for the hundreds of LGBTQ New Yorkers who spontaneously decided to fight back on a summer night in 1969 outside the Stonewall Inn. Afterward, for those that carried the gay liberation movement into the next decade through relentless organizing, innovative direct action, and sometimes literally screaming for their lives, the fight would stop for nothing.

As the highly-anticipated 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising was approaching in the spring of 2019, New York City made a huge announcement: Statues of queer NYC legends Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, two LGBTQ and civil rights activists who fought from the 1960s until their deaths, would be mounted in Ruth Wittenberg Triangle, just blocks from the gay bar turned national monument. This again raised questions about the fuzziness of what occurred in downtown Manhattan on June 28, 1969, when a routine and corrupt police raid birthed a still-burning movement. More hand-wringing about what role these women actually played that night ensued, with dozens of investigations, think pieces, and op-eds published ahead of the semicentennial of the historic events that night on Christopher Street.

It seems that Rivera and Johnson, who were, respectively, a teenager and a 24-year-old as they became intrinsic to the gay liberation movement’s story, weren’t actually at the Stonewall Inn when the fierce pushback against that bogus police raid of the mafia-owned bar was ignited. Johnson said later that she’d in fact arrived at 2 a.m. to find the bar set on fire by the NYPD; she then headed up to midtown Manhattan to find Rivera, who was asleep on a park bench. Nevertheless, the story of a defiant Johnson “throwing the first brick” at arresting cops has persisted. While who ignited the crowd remains a hot topic, it’s beside the point; myth-making in origin stories of social movements is fluid and drawn from memory and emotion. But the work over the following years is what truly changed the country for millions.

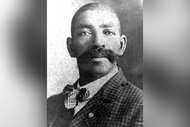

Marty Robinson, a former construction worker from Brooklyn, was there at the Stonewall in the early hours of June 28, 1969. A staunch activist who at that point was a member of the Mattachine Society, an early organization seeking rights for gay men, Robinson may have contributed to the making of the Stonewall legends. He was reportedly one of those who’d said it was Johnson who had hurled the “shot glass that was heard around the world" at the burning bar in a moment of rage and indignation. But it’s really what he did in the years after the uprising that helped galvanize a mass movement by co-founding the Gay Activist Alliance six months later and then shocking the nation with novel, attention-seeking protests that deployed disruptive tactics that became known as “zaps.”

“Stonewall would mean nothing if it had not led directly to the gay liberation movement, for it was that movement that broke the dam and set us free,” historian David Carter, who wrote the book “Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution,” said in 2004. “In my view, it was [the Gay Activist Alliance] more than any other organization that made the gay liberation movement spread — and Marty Robinson was the primary genius behind that organization. I'm told that at the end of his life Marty felt embittered over how history had largely ignored him and therefore did not preserve his own papers so that few of them have survived.”

The Gay Activist Alliance was founded six months after Stonewall, on Dec. 21, 1969, by seven men and women. It was launched as an offshoot of the more left-leaning Gay Liberation Front, which was focused on other issues like the ongoing war in Vietnam. Their goal was to center a single issue with a politically neutral organization to "secure basic human rights, dignity, and freedom for all gay people." Essentially, the group set out to work within mainstream politics to affect change. But the GAA was not timid. Protests of bar raids began almost immediately, and within a year the group was publishing the Gay Activist newspaper and aligning with other groups to launch the Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade, which grew into the massive Pride Parade and events that New York now has annually on the last Sunday in June. Robinson was the leader of the inaugural march in 1970.

However, the GAA and Robinson may be best known for popularizing “zaps” — a tactic credited to the young activist, later dubbed “Mr. Zap,” in which activists would abruptly interrupt public events to draw attention to the LGBTQ movement. An early zapping victim was New York Mayor John V. Lindsay, who was interrupted at a ceremony for the Metropolitan Museum of Art's 100th anniversary. Since he refused to meet with gay rights leaders or even acknowledge the growing movement, activists heckled him relentlessly and bombarded his events with literature. It worked — he met with LGBTQ activists and supported a 1971 anti-discrimination bill.

One highly publicized zapping took place at the headquarters of the New York Republican State Committee in Manhattan on June 24, 1970. There, GAA activists protested against Gov. Nelson Rockefeller and his silence on the rights of LGBTQ New Yorkers.

“We want (Gov. Nelson) Rockefeller to come out and fight for homosexual rights. Rockefeller is guilty of a crime of silence, and we are not leaving until we get a satisfactory answer to our demands,” the GAA’s Arthur Evans reportedly shouted.

After several hours of loud and disruptive demonstration, the annoyed GOP members had five people from the GAA zapping arrested. They were cheered as they were removed; months later, all of the charges against them were dropped. The Rockefeller Five are considered the first LGBTQ protesters arrested for gay rights in New York City.

“We are trying to use political power to achieve changes that will benefit homosexuals in the state. We want homosexuals to know who has been responsible for inaction regarding their civil rights,” Robinson told reporters after leaving the courthouse.

After such a highly publicized moment, zapping became a major piece of direct action campaigns and particularly during the GAA’s primary years of activity, which were until 1974; they also grew more targeted and grandiose. Private investigation firm Fidelifacts was zapped in a costumed protest, with activists dressed as ducks outside their after the company that was accused of targeting LGBTQ New Yorkers; the company president had said that while zeroing in on gay folks, “if it looks like a duck, walks like a duck, associates only with ducks and quacks like a duck, he is probably a duck.” Additionally, activists clogged company phone lines, shaming the company for its vile tactics.

While some understandably saw zaps as rude or juvenile, they tended to work. In addition to pressuring Mayor Lindsay’s anti-discrimination vote, an on-air evening news zap for low coverage of the movement, and appalling portrayals of LGBTQ folks, CBS News began to devote more time to covering the topic. The eye-catching actions — including the notorious 1977 pie served straight to anti-gay crusader Anita Bryant’s face — were also effective in recruitment. By the end of the decade, around 2,000 LGBTQ groups are believed to have popped up nationwide.

In addition to his dedication to the GAA, the prolific Robinson also founded The Lavender Hill Mob, an early AIDS activist organization; he was also a founding member of The National Gay Task Force and of The Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation.

After nearly three decades of activism, Robinson died of AIDS-related complications in 1992; he was 49. Later that year, Johnson's body was discovered floating in the Hudson River. Rivera died in New York of liver cancer in 2002.

While the coronavirus pandemic has forced New York City's long-running annual Pride Parade — an event whose inception is tied to the lives of all three activists and everyone who fought back against LGBTQ oppression — to be hosted largely virtually this weekend, the anti-corporate Queer Liberation March, which also shuns the presence of the NYPD, is set to kick off at 2:30 p.m. on Sunday from Bryant Park.