Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

The Hidden Story Of The Black Woman Behind The Prosecution Of One Of America's Most Notorious Mob Bosses

This year marks the 86 anniversary of the conviction of Charles "Lucky" Luciano. Eunice Hunton Carter is the Black woman who found a way to take him down.

In honor of Women's History Month, Oxygen.com is highlighting the contributions of trailblazing women in criminal justice.

America’s most notorious mobster Dutch Schultz was dead. It was 1935. His fellow crime lords, including Charles “Lucky” Luciano and Frank Costello, were behind the hit.

Schultz was considered too dangerous.

He wanted to kill Special Prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey. Luciano and the others believed that would cause more problems than it solved, turning up the heat on the mob and their illegal activities.

Shultz was shot in the men’s room of a New Jersey restaurant, two days before Dewey’s execution was set to take place.

Only Meyer Lansky cautioned against the idea, writes best-selling author and Yale Law School professor Stephen L. Carter in Invisible: The Forgotten Story of the Black Woman Lawyer Who Took down America’s Most Powerful Mobster.

“If Dutch is eliminated. You’re going to stand out like a naked guy who just lost his clothes,” Lansky told Luciano, according to Carter.

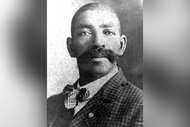

Luciano was “considered the Father of modern organized crime,” Marilyn S. Greenwald, the co-author of Eunice Hunton Carter: A Lifelong Fight for Social Justice, told Oxygen.com.

Schultz, Luciano, Costello, and Dewey are all part of America’s lexicon on crime. But there’s a hidden figure in this story, whose name should be included in that list: Eunice Hunton Carter.

“Eunice Carter was a brilliant lawyer who more than held her own among the best and brightest legal minds of her generation. She was the master mind behind the legal strategy that convicted Lucky Luciano and enhanced the national reputation of Thomas Dewey. … Yet for all of her undeniable merit and extraordinary achievements, Miss Carter was paid far less than her white male counterparts and she was never able to achieve her dream of securing a judicial appointment,” Janet DiFiore, chief judge of the New York Court of Appeals, said during a presentation by the Historical Society of the New York Courts in 2020.

She was the first Black female prosecutor in the United States. Dewey hired a team of 20 lawyers to help him take down the mob, Carter was the only woman and the only African American among them.

The New York Times announced her appointment with the headline: “Dewey Gives Post to Harlem Lawyer.” The subhead added: “Naming of Mrs. Carter, Negro, as Aide Viewed as Move to Break Policy Racket.”

When a character inspired by Carter appeared in HBO’s award-winning drama, "Boardwalk Empire" in 2014, people mocked the depiction as a Hollywood fantasy. A Black woman working as a prosecutor in the 1930s seemed unbelievable, but it was fact.

With Schulz dead, the ambitious Dewey, who would go on to become governor of New York and run for president twice, nearly defeating Harry S. Truman in 1948, needed another target and Luciano became public enemy number one.

Eunice Carter gave Dewey the keys to take down Luciano.

“On the beach one day, eight-year-old Eunice told a playmate that when she grew up, she wanted to be a lawyer,” Carter writes of his grandmother. “When he asked why, she explained that she wanted to make sure the bad people went to jail.”

Carter, the grandchild of slaves, had already accomplished much before joining Dewey’s team, moving in social and academic circles that included the who’s who of her era.

She graduated from Smith College in 1921. She was only the second woman in the school’s history to receive both a bachelor’s and master’s degree in four years.

The then governor of Massachusetts and future president, Calvin Coolidge, was her “friend and advisor.” When the Nobel Prize-winning scientist, Marie Curie, visited the college, Carter served as one of the hostesses, according to her grandson.

Two years later, she was one of the bridesmaids at Mae Walker’s wedding, the granddaughter of Madam C.J. Walker, the first Black woman to become a millionaire in the U.S.

Carter attended Fordham Law School while married and raising a toddler, graduating in 1932.

“By her own account, Eunice found the law fascinating. She loved the intellectual challenge,” Carter writes. “The study of law brought to her powerful mind a necessary discipline.”

Two years after graduating from law school, she ran for the state assembly, but lost. She went into private practice, but work was scarce. Eventually, she became a part-time “volunteer assistant” for the Women’s Court, where most of the cases involved prostitution.

She was regulated to the back of the bus after joining Dewey’s team, but she would refuse to stay there.

Carter got stuck investigating prostitution, which Dewey had no interest in pursuing. He wanted to focus on murder, extortion, loansharking, and drugs.

Greenwald told Oxygen.com that Dewey was also leery of being seen as picking on vulnerable women. Many of the prostitutes were drug addicts and poor.

He also didn’t want the public to view him as a “morality warrior,” writes Carter.

“No matter what story Dewey might have told about why he hired Eunice, the truth was that in assigning his lone female assistant to the prostitution angle, he was as much as telling her that she would do no important work,” Carter writes.

The public wanted to rid their neighborhoods of brothels and streetwalkers. Eunice was stuck listening to their complaints, and she was bombarded with them. People would walk in off the street to the Woolworth Building on Broadway, and eventually be directed to Carter.

It may have been a second-tier assignment, but Carter managed to find a link between prostitution and the mob. After reviewing court documents, she noticed a pattern, Greenwald writes.

Many of the prostitutes were represented by an attorney named Max Rachlin. The bond applications were signed by Jesse Jacobs or others likely related to him. She shared her theory with another member of Dewey’s team, Murray Gurfein. They went to Dewey, but he was skeptical.

The women were rarely convicted, but they were forced to pay a protection fee upfront from their earnings.

Carter did not give up and eventually Dewey agreed that the mob was involved in prostitution.

On Feb. 1, 1936, police conducted a massive raid of brothels across the city. Hundreds were arrested. It was Eunice Carter’s job to log and tag the women as they got to the police stations, Carter writes.

The raid produced a treasure trove of leads and witnesses and Luciano emerged as a prime suspect.

“As one magazine article noted, Luciano was to the prostitution industry as John D. Rockefeller was to petroleum,” Greenwald writes.

Luciano was a suave and debonair figure, unknown to the public, especially compared to Schultz, but that’s the way he wanted it, according to Greenwald.

He favored “handmade European suits and shoes, expensive cars, a private plane, and a lavish $7,600-a-year three-room suite in the Waldorf Astoria.”

“He was … calm and firm in times of danger, never emotional or flighty. … He always thought before he spoke. … He was never stingy with his money but cultivated the free and easy generosity of a gambler. That made him popular,” Hickman Powell wrote in his 1939 book Ninety Times Guilty.

Carter also played an important role in getting the women to open up and talk.

Greenwald notes that the other investigators on Dewey’s team “approached the women with a tough and threatening attitude, while some wouldn’t come close to them without wearing gloves.”

But the women trusted Carter. She made sure they were treated well in prison, purchased clothes for them and arranged for them to see family members, Greenwald said.

The trial started in May of 1936, and less than a month later, Luciano was found guilty of more than 60 counts of compulsory prostitution and sentenced to 30-to-50 years in prison.

Carter notes that Eunice had no formal role during the trial. When she did appear in court, she sat among the spectators.

“New York’s most important prosecution in decades was being tried according to her theory, and although Eunice was known for her poker face, she would not have been human had she not chafed at her exclusion,” Carter writes.

He writes that his grandmother became one of the most prominent Black women in America after the Luciano trial.

“She would receive honorary degrees be featured in Life magazine, lecture around the world, be handed medals and plagues from civic organizations everywhere … [and] become a prominent and influential figure in the Republican party.”

But there was one thing that Carter desired above all, but never achieved – becoming a judge.

Yet, she never placed racism or gender as the reason for not reaching that goal. She blamed her younger brother, Alphaeus, and his ties to the communist party. He was under FBI surveillance for much of his life, according to Stephen L. Carter.

Alphaeus Hunton was sentenced to six months in jail in 1951 for refusing to reveal the names of the individuals who contributed to a fund that paid the bail for party leaders.

Eunice was not among the well-wishers who welcomed him home when he was released. Carter writes that the siblings never spoke again. He struggled to find work and left America for Africa in 1958.

The siblings died 10 days apart in 1970, both from cancer.

“Eunice Carter was indeed my grandmother, but I didn’t know anything about those things that she had done when she was alive,” Carter said during an address at Harvard Law School. “She died when I was a young teenager, and I knew her mainly as the scary old woman who was always correcting our grammar and correcting which fork, we used when we ate and only after working on this book did I understand what she had done a long time ago. I came to understand that what I had seen as intimidation was really the kind of fortitude that she needed to accomplish the things that she did.”