‘People At The Time Did Not Tell The Truth’: Math Teacher Caught In Cold Case Murder

A wild party in Mission Viejo, California ended with Steven Merritt being shot to death.

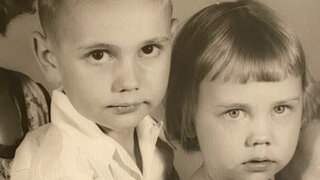

Steven Merritt’s mom, Anna Erickson, wondered why her son didn’t attend her birthday celebration in Mission Viejo, California, in February 1989. The next day, she learned the awful answer: He had been shot to death. And it would be 10 more long years before she would see justice served.

Merritt was a 21-year-old student who enjoyed partying and working on cars with his friends. On the night of Feb. 25, 1989, Merritt and a few of his friends were enjoying a keg when they heard word of a bigger party in the neighborhood. Despite not knowing anyone there, they lugged their keg over and were welcomed in, according to “Murdered by Morning” on Oxygen.

Merritt’s friend Chris Manfredi told producers that he didn’t remember any serious conflict at the party that night, other than his group at one point changing the music from salsa-style dance to something a little more rock-and-roll. Everyone in that group except Merritt left the party around 10 p.m.

“It wasn’t really our scene,” Manfredi said.

Merritt stayed behind until close to 3 a.m., talking and sharing dances with a girl he had just met. He called a friend to pick him up, asking to meet him at the intersection of Oso Parkway and Felipe Road. His friend waited, but Merritt never showed up.

A witness nearby heard shots, followed by squealing tires around 3:30 a.m., and police responded around 5. Merritt lay face down in the street, shot four times in the back. There was still cash in his wallet, but his ID was gone, so he went to the medical examiner’s office a John Doe.

Later that same day, Erickson was trying to figure out where her son was — he never missed a birthday. She called him at home with no answer, then spoke with his friends, who said they hadn’t seen him since the party the night before. Then, she called hospitals and morgues, as a sinking feeling set in.

When she filed a missing persons report, investigators quickly took notice. Sgt. Thomas Giffin, formerly of the Orange County Sheriff’s Office, went to Erickson’s home and showed her a picture of the body. She identified the John Doe as her son, Merritt.

Investigators then spoke with Merritt’s friends. One indicated that Merritt may have been dancing with the girlfriend or ex-girlfriend of Mark Morales, who hosted the party.

Morales didn’t have a lot to share with investigators: He said he vaguely remembered some sort of a dust-up around the beer keg, but couldn’t remember his ex-girlfriend talking with anyone. Then, he suggested that his Colombian-born roommates Alex and Mabel may have been involved in drugs — and potentially, Merritt’s murder.

The roommates couldn’t ID Merritt, but gave terse enough answers to make investigators suspicious. They knew they were onto something and decided to keep close tabs on Morales. A tip came in from a neighborhood grocery clerk who was heading home around the time of Merritt’s killing. The clerk claimed to have been disturbed when he saw a pedestrian walking down the road with a car deliberately trailing him.

The witness was only able to grab the last three characters of the license plate: NCK. Investigators ran those characters, and found a vehicle matching the witness’ description registered to Morales. Their only suspect had reported the car stolen on the morning of Feb. 26. It was soon recovered off a dirt road in Mission Viejo, totally burned. An accelerant had almost certainly been used, authorities told “Murdered by Morning.”

But when authorities went back to Morales, he and his family had lawyered up and refused to talk. There wasn’t enough probable cause for an arrest, so the case was shelved. In 1992, one of the lead investigators was transferred to another department, and Erickson was left to sit for years with her questions and her grief.

Eight years later, in 1997, a ray of hope appeared, when the sheriff’s department assembled a new cold case unit, which began sifting through reams of unsolved murders. Detective Brian Heaney picked up the Merritt case, and began to methodically re-interview witnesses. He found that several had different stories this time.

“People at the time did not tell the truth,” Heaney told the Los Angeles Times. “But with the passage of time, the burden of knowledge weighs on them.”

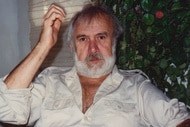

Heaney and other investigators found that Morales had fled the country after being questioned several times in the wake of the murder. He returned to the United States around 1993 and had gotten a job teaching middle-school math at a school near downtown Los Angeles, the Times reported.

This time, detectives got a clearer picture of what happened that night in 1989 — that Morales was enraged at Merritt for talking to his ex-girlfriend and the two even got into a scuffle at the party. Morales than followed Merritt, around 3 a.m., confronted him, and then shot him in the back as he tried to walk away.

On March 1, 2000, authorities, comfortable with the evidence they’d collected, made their move. They arrested Morales and took another run at a prior witness who they believed had helped Morales cover up the murder, this time offering immunity from prosecution — unless he perjured himself. Armed with the final pieces of the puzzle, prosecutors prepared a largely circumstantial, but compelling case, they told “Murdered by Morning.”

Morales finally went to trial in July 2003, with his defense team mostly attacking the credibility of the witnesses against him. Still the jury found him guilty and he was sentenced that November to 17 years to life in prison.

“It helps to know that someone is going to pay for taking the life of your child,” Erickson told producers. ‘Maybe that’s vengeance — I don’t know. I don’t care. We waited a long time to get justice, but we finally did.”

For more on the Merritt case, including how detectives used a wiretap to finally close in on Morales, watch “Murdered by Morning” at Oxygen.com, and airing Sundays at 7/6c.