Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

Brothers Behind Execution-Style Massacre In California Called A ‘Unique Breed’ Of Evil

Donald Young and his brother Timothy executed five people with shotguns in a California bar. An alleged accomplice claimed that the siblings followed that carnage with a triple homicide.

On July 18, 1995, three men walked into Pato’s Place, a quiet bar on the outskirts of town in Tulare, California.

They wore ski masks and carried shotguns. They demanded money from everyone inside and gathered about $300. Minutes later, the owner, Guadalupe Cantu, 43, was critically wounded and five others in the bar were dead.

Cantu, who’d been shot in the chest, pretended to be dead until the shooting stopped and the perpetrators left. He then managed to call 911.

Investigators described the crime scene as “horrific” and a place of “carnage.” It would take 10 years and another mass homicide before the Pato’s Place killers would be brought to trial.

At the saloon, each victim had been shot in the head and executed at point-blank range. The victims were Celia Martinez, 50, Armando Lugo, 22, Jorge Munoz, 23, Roberta Lynn Nunez, 39, and Margaret Moreno, 44.

“It was hard to walk around because of the amount of blood,” Wes Hensley, a detective with the Tulare Police Department, told “Killer Siblings,” airing Saturdays at 6/5c on Oxygen.

At face value, it appeared to be a robbery, Brian Moore, a detective with the Tulare PD, told producers. But investigators couldn’t understand why five people would be massacred.

Authorities searched for a motive. They spoke with Cantu as he recovered from his injuries, and learned he knew the victims. They were hard-working people, all in the wrong place at the wrong time, he said. Cantu was only able to provide a vague description of the killers, though.

“This was the biggest case in Tulare County history at the time as far as the amount of victims,” Brian Haney, a detective with the Tulare County PD, told producers.

Investigators dug into the case, collecting evidence at the scene, which included a shoe print on a bar stool. They canvassed the area and interviewed witnesses.

Few leads surfaced, so officials relied on the media and the community to spread the word about the crime. A day after the murders, phone calls came in as evidence turned up around the city.

Wallets, clothes, and shoes were found on the sides of roads in Tulare. Then, ski masks turned up — and then the shotguns. Authorities confirmed that the recovered guns were the murder weapons.

Detectives collected DNA material from the masks that was analyzed but there was no database to search for matches to track down suspects. The investigation stalled.

Six months later, a triple homicide in nearby Corcoran, Calif. in Kings County re-energized the Pato’s Place investigation.

In this case, three men had been shot at close range. The victims were Kimmy Jones, 34, Cesar Burgueno, 33, and Charles Shields, 24, and they'd all been shot twice in the head, the Associated Press reported in 1999. Jones’ history with narcotics led officials to consider that the slayings were connected to a drug hit.

Dave Putnam, a detective for Kings County Sheriff’s Department, told producers that the brutal crime scene had the look of an execution homicide. The perpetrators’ philosophy appeared to be not to “leave anybody alive that could be a witness.”

Mass murders were a rarity in Tulare and Kings Counties, so investigators considered that the triple homicide in the residence could be connected to the Pato’s Place massacre.

Authorities from each county worked as a team, conducting surveillance, doing interviews, and comparing notes each step of the way. But 18 months later, officials hit a wall.

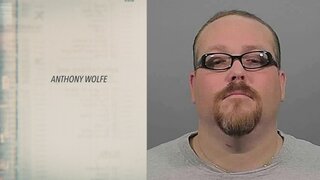

In February 1997, nearly two years after the Pato’s Place slayings, investigators got the lead they needed when Anthony Wolfe was arrested for fraud. Wolfe wanted to bargain for leniency and said he had information about the Pato’s Place homicides — because he was there.

Investigators were skeptical, but when Wolfe described how one of the perpetrators jumped over the bar, they realized he had inside information. Detectives had never made the detail public. He was offered immunity in exchange for charges in an unrelated counterfeiting case being dropped, the Hanford Sentinel reported in 2005.

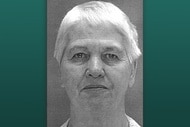

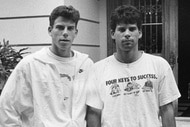

Once the deal was struck, Wolfe spilled everything. He claimed that the killers were Donald and Timothy Young, brothers who’d grown up in Lemoore, Calif. After high school the Young brothers struggled, going from job to job and eventually falling into criminal ways that got increasingly more serious.

Wolfe described how the robbery and murders went down at the bar. After he and the brothers fled the scene, Wolfe said Donald reminded him that they knew where he and his grandmother lived to ensure his silence.

This confession broke the case “wide open,” detectives told producers.

The brothers, who’d previously done time, weren’t incarcerated when the second round of mass murders occurred. That meant that they could have been the killers. However, the siblings also had alibis for their whereabouts during the Corcoran murders. They’d both been at a party, they said.

As with the Pato’s Place crime, an alleged accomplice with criminal history soon came forward as a witness.

In December 1998, Michael Horbert, 34, told authorities that Donald and Timothy Young entered the Jones residence to steal drugs. As he waited in the getaway car, Horbert said he heard gunshots from inside, and then the Youngs came back to the car with drugs they’d taken.

Meanwhile, DNA evidence on the ski masks and a recovered shoe tied the brothers to the Pato’s Place crimes. Almost four years after the homicides at the bar, investigators were finally able to obtain arrest warrants. The brothers were charged with five counts of murder and one count of attempted murder.

After years of legal stalling by the Youngs, who “knew how to work the system,” as the daughter of a Pato’s Place victim told producers, the trials for Donald Young, 36, and Timothy Young, 35, began in September 2005. More than a decade had passed since the Pato’s Place homicides.

“It was going to be a hotly contested battle,” defense attorney Galatea Delapp told producers.

But Wolfe, whose credibility was a concern, turned out to be an effective witness for the prosecution. Plus, the DNA evidence was solid.

In December 2005, the Young brothers were convicted of murdering five people. They were sentenced to death in 2006. The second trial for the murders in Kings County was abandoned.

Whether you call the Young brother serial killers or mass murderers, Hensley told producers, they’re part of a “unique breed capable of that kind of evil.”

To learn more about the case watch, “Killer Siblings” on Saturdays at 6/5c on Oxygen, or stream episodes on Oxygen.com.