Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

100 Years Ago, An Angry White Mob Destroyed The Small Town Of Rosewood, And It Was Nearly Forgotten

100 years after the Rosewood Massacre, descendants of victims and survivors work to ensure that America remembers the tragedy.

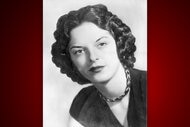

It started with a lie. More than 100 years ago, on the first day of the new year of 1923, Fannie Taylor, a white woman, claimed a Black man assaulted and attempted to rape her. Within hours, hundreds of angry whites invaded the small and mostly Black town of Rosewood in Florida.

One week later, the town of Rosewood was gone, only the ashes remained, eight people died — six Black and two white, but others maintained that the number is much higher and that somewhere in Rosewood today is a mass grave with dozens of victims buried there. Most of the Black residents who survived fled through the swamps or by train.

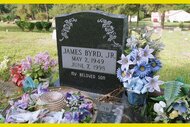

RELATED: Emmett Till’s Family Demands Arrest Warrant Served In 1955 Lynching In New Lawsuit

“What we know is that a lot of people disappeared, mainly men, and their families never heard from them again,” Maxine Jones, a professor of history at Florida State University, told Oxygen.com. “We don’t know if they were killed and their bodies were never found or if they just disappeared or they didn’t return for the safety of their families.”

Jones, the principal investigator of a report in 1993 on Rosewood, which was commissioned by the Florida Legislature, said that they were only able to confirm the eight deaths.

But the legacy of Rosewood is about more than a bloody and deadly rampage, it’s about the loss of generational wealth, divided and broken families and generational trauma.

“It’s such a powerful example of the complete and total annihilation of a Black community,” Marvin Dunn, historian and professor emeritus at Florida International University, told Oxygen.com. “It’s happened before, but this is a very rare event for an entire Black community to disappear like Rosewood did.”

Jones said acknowledging the history of Rosewood is important to healing.

“We have to acknowledge it, and we have to make sure it never happens again,” Jones said. “I think we can use the past to help us map a better future. I think Rosewood helps us to understand some of the tension, distrust and fear among Black and white people in this country.”

On Jan. 8, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the massacre, descendants of the victims and survivors of Rosewood gathered and held a wreath laying ceremony. Other events were also held days before.

“This is important emotionally, not just historically. People were crying out there just to be able to walk on that land,” Dunn said. “People were overwhelmed to be able to sing and pray together and talk. There were a lot of tears, weeping and hugging. It was if the ancestors were speaking to us, saying, 'Welcome back. Thank you for coming home. We’re still here.'”

Rosewood occurred during a period of rampant racial unrest in America. Black men returned from serving in War World I expecting to be treated as first-class citizens, but faced a resurgent Ku Klux Klan, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

Over a period of nearly 10 years — between 1917 and 1927 — 454 people died from lynch mobs, and 416 of them were Black, according to the Rosewood report.

Two years before Rosewood, in May of 1921, a white mob destroyed a thriving Black community in Tulsa, Oklahoma, known as “Black Wall Street,” burning it to the ground and killing hundreds, wiping out generations of Black wealth.

“The loss in Tulsa and in Rosewood, those are very similar losses because so many Black people lost land, and land is the basis of generational wealth,” Dunn said. “We as Black people are essentially landless people. When you have a huge swath of privately owned Black land taken through racial violence, that’s a very, very big story that’s going to last generations.”

Jones makes a similar point about the economic consequences of the Rosewood tragedy.

“If Rosewood had not been destroyed, the families would have passed their land and their legacy on to their children and their children’s children. And they were denied that,” Jones said. “Rosewood is just one of many such incidents that happened in this country.”

One month before the Rosewood massacre, in Percy, Florida, a white school teacher was murdered by an escaped convict. A group of whites, some from Georgia and South Carolina, removed the suspect, Charles Wright, and his accomplice from the jail. Wright was severely beaten to get him to confess and implicate others, according to the Rosewood report.

Wright refused to implicate anyone else in the murder and was burned at the stake. Two other men, suspected of being involved in the murder, were shot and hung. They were never implicated in the crime.

But the mob was still hungry for vengeance, burning down a Black church, masonic lodge, amusement hall and Black school.

“Black residents of the area seemed to understand that they were sitting on a tinder box that might well explode again at any moment. In less than a month, the Black community of Rosewood felt the iron hand of the white mob,” researchers wrote in the 1993 paper.

The white community believe that a Black man attacked Fannie Taylor, but Black residents told a different story. In their version of events, she was beaten by her white lover and accused a Black man to cover up her alleged infidelity.

One month after the deadly rampage, a grand jury was convened. The proceedings ended after one day because no one was willing to testify, Smithsonian Magazine reported.

The Rosewood Massacre all but vanished from the official record, much like the town. Many of the Blacks who witnessed and survived the violence were intimidated into silence.

“Fear is very powerful and the reach of powerful white people was very long, and so they knew that they couldn’t talk about this. Some of them didn’t even talk about it among themselves,” Jones said. “And when some of the families started talking about it, it was not for outside consumption. It was to be talked about only among family members.”

Decades later, a new generation decided it was time for them to share what they knew of the tragedy.

Lizzie Jenkins was just 5 years old in 1943 when her mother told her about the Rosewood race riots, gathering her and her three siblings in front of the fireplace.

“My brother and I were so upset. Here I was 5 years old, trying to bear the burden of history,” Jenkins told Oxygen.com.

Her aunt, Mahulda Gussie Brown Carrier, the Rosewood school teacher from 1915 to 1923, was beaten and gang raped by a group of white men because she refused to say her husband was not home on the day Taylor was attacked, Jenkins said.

“I took that story with me. I took it to college with me. After college, I took it to work with me,” Jenkins said. “It became mine and my mother’s story. We never talked about it in public. It was private. It was our secret because my aunt was still on the run. she lived a miserable life.”’

Jenkins said her aunt and her husband, Aaron Carrier, who was nearly beaten to death during the massacre, moved over 15 times, changing their names. Visits to their family in Archer, Florida were made under a cloud of secrecy.

She said her aunt was tormented by those who wanted her to stay quiet.

“My mom said we must tell her story, so it became my story,” Jenkins said.

Now 84, Jenkins has spent her entire life making sure people learn about and remember Rosewood. She founded the Real Rosewood Foundation. She has a podcast and has written a children’s book about the massacre.

“This is my life. This will take the rest of my life. It’s not easy. It is painful. This story must be told. It’s very, very much needed for the next generation,” Jenkins said.

Gregory Doctor’s family operated under a code of silence about Rosewood. His grandmother Thelma Evans Hawkins survived the massacre as did several other family members. He said his family not only lost land, but family ties were broken because people lost contact. Names were changed.

“My grandmother had the code of silence. I could see that she was depressed all the time. I didn’t understand why, but she would sit on the porch and sing her gospel hymns. She was singing from pain,” Doctor told Oxygen.com. “My grandmother never left the house without her pistol. She slept with that pistol. She went to the bathroom with that pistol. She would be doing general house chores and her pistol would be close by. That was all out of fear.”

Doctor’s organization, the Descendants of Rosewood Foundation, held several events commemorating the centennial anniversary including the wreath laying ceremony.

His cousin, Arnett Doctor, led the fight for compensation or reparations for the victims, which the state of Florida approved in 1994.

“I called him the Moses of the family,” Doctor told the Tampa Bay Times about his cousin Arnett. “God implanted in him the spirit to lead the family and fight for reparations.”

Some 60 years after Rosewood, Arnett helped reporter Gary Moore reveal the story in 1982 in the then-St. Petersburg Times.

“I called my editor and told her that I had a story about a whole community vanishing” Moore told Smithsonian Magazine. “She was shocked.”

One year later, "60 Minutes" did a report with the late Ed Bradley.

“A lot of family members weren’t pleased about that because they wanted to take this to their graves, even the second generation because that’s what their parents had instilled I them, so it’s a lot,” Doctor said.

The Florida legislature passed a $2 million compensation plan in 1994. Nine survivors were awarded $150,000 each. The bill also provided a scholarship fund for families of survivors and their descendants according to the Washington Post.

Nearly 300 students have received Rosewood scholarships, according to data compiled by the newspaper in 2020.

Jones said that the survivors sharing what happened to them was perhaps more important than financial compensation.

“This is one of the gifts that came out of this is that for the first time, they had an opportunity to tell their story,” Jones said. “They had a voice. That voice had been taken away from them, and now they had it back.

“And to watch them tell their story was riveting. It was heartbreaking. It was wrenching as they described how they were forced to go into the swamps where it was wet and cold that first week of January. They finally had a voice. They finally got to tell their story.”

The late director John Singleton depicted the massacre in his 1997 movie "Rosewood," which starred Don Cheadle, Ving Rhames and Jon Voight.

The history and legacy of Rosewood is complicated and not everyone is happy that after years in the dark, the story is getting light.

Dunn, who owns five acres of land in the town, was the victim of an apparent hate crime in September of last year. A man was arrested and charged with aggravated assault. He reportedly screamed the N-word at Dunn and six others, and nearly hit Dunn’s son with his truck. Dunn said that the FBI is also investigating the incident.

He purchased the land in 2008, and wants to give it to the state or buy more land and create a national park.

“I want the state of Florida to take these five acres and make it a state park,” Dunn said. “This gutted soil needs to be preserved for history. People need to be able to come to Rosewood and walk on this unmolested land.”

Jenkins is also working to preserve the history of Rosewood for future generations. She plans to move the house that once belonged to John Wright and his wife, to her hometown of Archer and create a museum.

Wright, a white shopkeeper, hid women and children in the attic of the house for two days during the bloodshed until they were able to safely catch the train out of town.

Jonathan Barry-Blocker, a law professor, learned about his family’s ties to Rosewood when the movie came out. He was 13 years old. His late grandfather, Rev. Ernest Blocker, survived the massacre and held a five-minute discussion with him and his siblings once about the incident when the movie was released.

Barry-Blocker told Oxygen.com that he does not remember much about the conversation and that his dad had to remind him that it even took place.

He has spent the last few years finding out more about his family history — Rosewood and beyond.

“I think I’m like a lot of Black Americans, I want to fill in the gaps in my family legacy,” Barry-Blocker said. “It’s not always easy for us to track down who our progenitors were — where they were or what they did.”

He told the Southern Poverty Law Center that he was angry when he came to understand his family’s history.

“The thoughts in my head were: Was my grandfather one of the children screaming amid the violence? Did they have to jump onto that train? Were they in that swamp? And what could have been,” Barry-Blocker said. “Rosewood was a pretty wealthy Black town for the turn of the century. Could my family have built some homeownership, land holdings? Could they have gone to college sooner? After Rosewood, they had to start all over. They had to start from the bottom in a sense, in a place where they had no footing. ... What would have accrued to them until now, but for the attack on Rosewood?”

He was among the hundreds at the wreath laying ceremony, along with his two young children.

Barry-Blocker is already sharing the story of Rosewood with his 4-year-old daughter.

He explained to her where they were going and why, answering her questions on the day of the wreath laying ceremony.

“I put it on her radar, and as she gets older and has a better understanding of the world and of people, I will give more details and share more facts. I don’t plan to keep them in the dark. I don’t want them to be misinformed about who their progenitors were and what they did, not all of us are sharecroppers, not all of us are destitute, not all of us were illiterate, not all of us led tragic lives,” he said. “There was joy. There was success. There were achievements. There was innovation. I want them to understand that is there inheritance as well, not just pain and suffering.”