15-Year-Old Claudette Colvin Refused To Move To The Back Of The Bus Before Rosa Parks

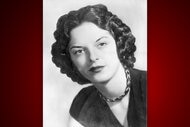

Nine months before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of a Montgomery, Alabama bus, a high school student named Claudette Colvin made a similarly pivotal decision in the fight for civil rights.

Nearly 70 years ago, nine months before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of the bus, a 15-year-old Claudette Colvin staged a similar protest — but it would be decades before much of the world learned of her heroic actions.

“I don’t see myself as a hero because I’m just an average woman,” the now 83-year-old Colvin told Oxygen.com. “I did play a significant role [in the Montgomery Bus Boycott] but there were so many other people ahead of me, and so many people who have never been recognized.”

On a warm spring day on March 2, 1955, a then-15-year-old Colvin was riding the bus home from school with her classmates in Montgomery, Alabama. The bus became crowded, with Black and white passengers forced to stand. The bus driver told Colvin and her three classmates, “I need those seats,” Phillip Hoose wrote in the award-winning "Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice."

Colvin’s classmates quickly surrendered their seats, but Colvin refused to move. She told Hoose that she was aware of the rule that Blacks did not have to give up their seats if the bus was filled.

“But it wasn’t about that. I was thinking, 'Why should I have to get up just because a driver tells me to, or just because I’m Black?' Right then, I decided I wasn’t gonna take it anymore. I hadn’t planned it out, but my decision was built on a lifetime of nasty experiences,” she recounts in the book.

Some of the injustices included being unable to try on clothes in the store, the system of separate but unequal. Several years earlier, a popular classmate, Jeremiah Reeves,16, was unjustly convicted and sentenced to death by an all-white jury for raping a white housewife. Police had coerced a confession from him, which he later recanted. She wrote letters to him in prison and helped collect money to pay for his legal defense team. A then 25-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. and the NAACP were also among those fighting for his freedom.

"In the years that he sat in jail, several white men in Alabama had also been charged with rape; but their accusers were Negro girls. They were seldom arrested; if arrested, they were soon released by the grand jury; none was ever brought to trial. For good reason the Negroes of the South had learned to fear and mistrust the white man's justice," King wrote in his memoir, "Stride Toward Freedom."

Reeves was executed in 1958.

Colvin, a student at Booker T. Washington High School, was also inspired by studying Black history weeks prior to her protest and the people who fought to improve the lives of African Americans including Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth. She also studied the U.S. Constitution.

“All the injustice was running through my head that day. If felt like history had me glued to my seat,” Colvin said. “It felt like Harriet Tubman’s hand was on one shoulder and Sojourner Truth’s hand was pushing me down on the other. I was paralyzed in that seat. I could not move if I had wanted to.”

Colvin noted that there was also a spiritual presence moving her to stay seated.

She said in an affidavit to have her record expunged that when a white person said she had to move, her friend yelled back, “She doesn’t have to do anything but stay Black and die.”

“I wasn’t afraid of death. My sister Delphine had died two years earlier on my 13th birthday,” Colvin said in the affidavit. “When you’re a teenager, death doesn’t scare you.”

The police were called, and Colvin was removed from the bus, arrested and placed in a jail cell.

“It just killed me to leave the bus. I hated to give that white woman my seat when so many Black people were standing. I was crying hard. The cops put me in the back of a police car and shut the door,” Colvin said in the book. “They stood outside and talked to each other for a minute, and then one came back and told me to stick my hands out the open window. He handcuffed me and then pulled the door open and jumped in the backseat with me. I put my knees together and crossed my hands over my lap and started praying."

Weeks later, she was found guilty of violating the segregation law, disturbing the peace, and assaulting one of the police officers. She was placed on probation. The segregation conviction was overturned on appeal.

But Colvin was not done fighting injustice. Two months into the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Colvin, by then five months pregnant, agreed to become one of four plaintiffs — along with Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald and Mary Louise Smith — in Browder v. Gayle.

In November of 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court would uphold a lower court ruling that bus segregation was unconstitutional.

Legendary civil rights attorney Fred Gray represented Colvin during her arrest and in the landmark segregation case.

"They had to literally drag her off the bus. They charged her with being a delinquent, but she was an honors student at Booker T. Washington," Gray told the Montgomery Adviser in 2019. "If Claudette had not done what she did, nine months before (Ms. Parks) ... She gave the moral courage to Jo Ann Robinson, to E.D. Nixon, to Dr. King. (You had) a 15-year-old girl who did what she did, and was willing to take whatever consequences, not knowing what was going to happen. When you compare it, Claudette had a lot more courage than many of us involved."

Colvin became known as “the girl who got arrested.” At first, her protest was celebrated, but slowly she was shunned and labeled a troublemaker. Eventually, she left Montgomery and moved to New York City, working as a nurse’s aide. She retired in 2004. Her role in the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the landmark Supreme Court has been overlooked, and Colvin made it a point to avoid the spotlight.

Decades later, she finally decided to share her story.

“I wanted people to know the truth. Most of the people I spoke to throughout the years in the North thought that Mrs. Parks just sat down on the bus, and they changed the laws,” Colvin said. “But that wasn’t so. It took a lot of litigation to take place to change things, and it took a lot of brilliant lawyers.”

She later added: “These laws were so brutally enforced. ... It was supposed to be separate but equal, but it was separate and unequal. Our community was targeted, and we were treated unfairly. Everything was handed down to us on a second-class level.”

Parks, older, married, and an NAACP activist, became the face of the movement and treasured civil rights icon. When she died in 2005 at the age of 92, her casket was placed in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol for public viewing. She was the first woman and the second African American to receive that honor.

Colvin’s contributions are finally coming to light.

“It was a story obviously worth telling and hearing. ... She risked her life for her community twice,” Hoose told Oxygen.com. “She risked her life and her family’s life to take a stand, and what really floored me is that she did it again, by agreeing to become a plaintiff in Browder v. Gayle.”

Hoose said Colvin was reluctant to share her story, and only agreed to work on the book after several years of conversations. The book was published in 2009 and went on to win the National Book Award among other honors.

Colvin said she waited decades to tell her story because of the climate in Montgomery.

“Everyday to me was a protest,” Colvin said. We were fighting every day for our lives, for survival. That’s why I never said anything.”

Sixty-six years after her arrest, Colvin sought to have her record expunged, which was granted by Judge Calvin Williams.

“My record was expunged, but I should never have been prosecuted anyway,” Colvin said. “I did not do anything wrong as a minor. ... Having my record expunged had me feeling like I was an 80-year-old teenager.”

Judge Williams, who is African American, also apologized to Colvin.

“In my mind, she’s a hero because I think Ms. Colvin provided the blueprint. She was the precursor and blueprint for what inevitably came to be the Montgomery Bus Boycott and eventually a national movement on civil rights,” Williams told Oxygen.com.

He said the apology was long overdue.

“I stated the significance is correcting an unjust act, but the symbolism of that I am the byproduct of her heroic act. ... It’s important because people need to understand that this was an effort on behalf of so many unsung and unrecognized heroes. Claudette Colvin just happens to be one of them.”

He later added: “But for her actions, we may not have gotten where we are today, and I certainly appreciate what she did and what she stands for today. She’s due to be appreciated and recognized for it.”

Many more people will soon come to know Colvin’s story. A movie called "Spark," based on Hoose’s book, is in the works. Saniyya Sidney, who played Venus Williams in the Oscar-winning film "King Richard," is set to star as Colvin. Actor Anthony Mackie will direct.

Mackie, who has appeared in the "Captain America" and "Avengers" movies, told Deadline that he discovered Colvin’s story while visiting the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis.

“Not only was I moved, I was inspired. It’s great to be a superhero in movies but she’s a real live one living amongst us and I’m honored to tell her story.”

Colvin said she wants the movie to show what life was like for 15-year-olds back then.

“When they tell my story I want them to show what it was like being a teenager. How teenage Black girls and boys were treated in the South,” Colvin said. “The courage it took for my family, my mother and father. How they helped me. How they came to my rescue when they saw what I was doing.”

“Children take everything for granted today They don’t realize how hard we had to fight, and some people lost their lives just for defying segregation.”

Colvin said she is most proud of raising two sons, her faith, and her role in the bus boycott, but wishes she had gotten the chance to travel more.

“When I was a little girl I wanted to travel. That was my dream. I didn’t really accomplish my dream. I would dream about these places that I would see in the picture book,” Colvin said.

As for the future, she wants more middle-class African Americans to help and uplift poor Black children. She also noted the need to improve the educational system.

“I would like to see the system provide better education for elementary school children. That’s where we have to start,” Colvin said. “You can’t wait until ninth or 10th grade. In this technological world, you need more than just a basic education. What got me through won’t get them through.

“Everyone cannot be a basketball player. Everyone cannot excel in sports and entertainment. We need more doctors. We need more scientists. We need more people in the medical field. ... Don’t bury the talent you already have. Multiply the talent that you have.”