Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

Did The For-Profit Company Maximus And The 'Poverty Industrial Complex' Fail Gabriel Hernandez?

Maximus, a for-profit company that helps run government services, comes under fire in Netflix's new documentary, “The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez"

Government programs like Medicaid and foster care are designed to help those in need — but as more local and state-run programs turn to for-profit-companies to help them operate, the focus can shift toward making a profit and children like Gabriel Fernandez suffer, as shown in the new docu-series "The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez

Daniel Hatcher, author of “The Poverty Industry: The Exploitation of America’s Most Vulnerable Citizens,” compared the growing trend to the “military industrial complex,” describing it in the new Netflix documentary “Trials of Gabriel Fernandez” as a “huge poverty industrial complex.”

"States and their human service agencies are partnering with private companies to form a vast poverty industry, turning America's most vulnerable populations into a source of revenue," Hatcher wrote in his book, according to The Atlantic. "The resulting industry is strip-mining billions in federal aid and other funds from impoverished families, abused and neglected children, and the disabled and elderly poor."

Companies known for integral roles in our country’s defense industry — like Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman — may also be contracted with the government to provide other services, like child support offices, Medicaid services, health insurance call centers and welfare-to-work programs. States turn to these private consultants and companies to develop strategies that reduce costs and maximize revenue.

“Northrop Grumman, in addition to building tanks, they are also making billions in contracts for state governments that are supposed to serve the poor, but their focus isn’t about what’s best for the poor, their focus is about the bottom line of their company,” Hatcher said in the series.

For-profit company Maximus specifically comes under fire in the series, which tells the harrowing tale of an 8-year-old boy who endured merciless abuse from his mother and her boyfriend until he was eventually beaten to death.

Many who knew Gabriel — including his teacher, grandparents and a security guard at a government services building — tried to alert authorities, calling an abuse hotline and 911 to report the suspected abuse. But despite repeated visits from both social services and the sheriff’s department, Gabriel remained in his mother’s care, where he was forced to eat cat feces, forced to sleep in a small, locked cabinet, shot with a BB gun, beaten and burned with cigarettes.

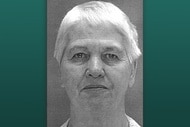

Gabriel died from the abuse in May 2013 and his mother Pearl Fernandez was later sentenced to life in prison after pleading guilty to first-degree murder. Her boyfriend Isauro Aguirre was found guilty by a jury for first-degree murder and torture and was sentenced to death.

The documentary focuses mainly on Gabriel’s short life and the horrific death he suffered, but it also calls into question the larger systemic failures that may have played a role in the 8-year-old’s death including the role of Maximus, the company contracted with Los Angeles County to help provide government services.

For the last four decades, Maximus has partnered with state, federal and local governments to help provide high-quality health and human service programs in "cost-effective" ways tailored to each community, according to their website.

"We offer governments the ability to implement programs rapidly with scalable operations and automated systems," they write on their site. "From Medicaid and Medicare to welfare-to-work and program modernization, our comprehensive solutions help governments run effectively and efficiently to achieve their goals."

Arturo Miranda Martinez, a former security guard at the Los Angeles County’s Department of Public Social Services Greater Avenues for Independence (GAIN) office, and who testified in Aguirre’s trial, said he was working at the office on April 26, 2013 when Pearl Fernandez came into the office with her children.

Martinez said as Gabriel walked by, he noticed cigarette burns — some fresh and some healing — on the back of the boy’s head and saw bruising around his eyes.

“I saw the marks and I said ‘Damn man, this is f---ed up. And that’s when it just hit me, 'Oh s--t, child abuse man,” he recalled in the docu-series. “Like, ‘Look what they are doing to me,’ that’s what he was saying. I mean his body was talking, yelling. He didn’t even really have to say anything. It was all over his body.”

Martinez said he tried to alert Marisela Corona, an employee at the office who had been trained in domestic violence. Corona wanted to report the suspected abuse but allegedly told Martinez that her supervisor wouldn’t let her because it was almost 5 p.m. on a Friday and they did not want to pay overtime, he said.

Martinez then called his own supervisor — who he claimed also encouraged him not to get involved — but he decided to place a call to law enforcement anyway to report the suspected abuse, providing the family’s name and address.

“If I can help someone, then I am going to go ahead and do it,” Martinez said.

Gabriel died 29 days after that call was made.

Maximus, the company who runs the GAIN office, has denied that any decisions were made based on overtime concerns and later told producers of the docu-series that Corona had contacted the sheriff’s office.

Producers of the series, however, said Corona never mentioned making a call in her initial statement to law enforcement and there is no record of the call.

“There’s no indication that she made any contact,” former Los Angeles Times reporter and series producer Garrett Therolf said.

When Hatcher was asked by a producer of the docu-series whether he would be surprised to learn that someone at the center had suggested they not make the call because they didn’t want to pay overtime, he said it wouldn’t be too surprising.

“No, because there have been claims against Maximus for not paying overtime in various states,” he said. “Cost-cutting, I think unfortunately, becomes a typical focus of the private companies.”

In 2014, employees of a Maximus-run call center in Boise, Idaho sued Maximus claiming the company mischaracterized their jobs and deprived them of overtime, according to the Idaho Statesman.

The large, multi-state company has faced criticism in other arenas as well.

In Kansas, employees filed a complaint earlier this month alleging that Maximus was misclassifying and underpaying its employees, according to Mother Jones. The news outlet reports that it is the 10th such complaint filed against the company since 2017.

The state hired Maximus in 2016 to help process Medicaid applications but after a backlog of as many as 11,000 applications prevented those in need of getting health insurance, the state sent the company a notice of non-compliance in January 2018.

Due to the large backlog and eligibility issues, Kansas decided to take back its complicated applications for the disabled and elderly and handle training and quality itself.

“MAXIMUS’ performance has not met our standards. There was a tremendous backlog developed due to understaffing. Additionally, oversight and training were lacking,” Jeff Andersen, secretary of the Kansas Department of Health and Environment, wrote in 2018 newsletter addressing the issue. “While the bid was appealing from a cost-savings perspective, you get what you pay for.”

Maximus later agreed to pay the state $10 million in concessions, Mother Jones reports.

A new report from the Government Contractor Accountability Project also found that "alarming numbers" of children lost health coverage through the state's Medicaid and CHIP programs in recent years after they were disenrolled from the programs, even though the children remained eligible.

"Problems at Maximus have at times directly impeded vulnerable Americans from accessing the health services that they desperately needed,” the 2019 report said. “Maximus has also been implicated in performance failures that affect the security of health system information, health care provider payments, and stewardship of public dollars.”

Other employees across the country, who worked at some of the company-run call centers designed to help people who have insurance through the Affordable Care Act, have tried to unionize with the Communications Workers of America (CWA), according to New York Magazine.

Many of the workers say they're paid just above minimum wage and struggle to pay for their own health care costs due to their high deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums. Workers told the news outlet they struggle to afford medical procedures, prescriptions and visits to health care providers.

“Maximus didn’t write the rules for the Affordable Care Act, but it is still speaking out of both sides of its mouth,” Kathleen Flick, who works in a call center in Louisiana, told the magazine. “Here we’re trying to help low-income people get coverage, and we can hardly afford our own coverage.”

Hatcher said one concern with third-party companies like Maximus is that the focus too easily becomes about profit rather than getting people the help they need.

Maximus received the nation’s first privatized welfare contract in 1987 from Los Angeles County and by 1990 had was generating $19 million in revenue, Mother Jones reported in 2019.

The company’s revenue continued to grow after President Bill Clinton ushered in welfare reform in 1996 and Maximus went public the following year. Ten years after the welfare reform, the company had an annual revenue of $701 million.

Over the last 10 years, Maximus has contracted with 28 states and Washington D.C. for $1.7 billion in services, according to an analysis by Mother Jones. More than 40% of the company's total revenue comes from its state contracts to provide government services, the report from the Government Contractor Accountability Project stated.

In a 2013, an assessment report from the Maryland Department of Human Resources carried out by Maximus, referred to foster children as a “revenue-generating mechanism,” Hatcher pointed out in the docu-series.

“I think it’s a very unfortunate example of where you have a contract that is ultimately focused on profit rather than maximizing the well-being of vulnerable people who need the services,” he said.

In a 2018 article Hatcher wrote for The Cap Times, he accused the company and the state of Wisconsin of identifying foster children who are disabled or have dead birth parents to apply for the children’s social security disability and survivor benefits and establish the state as the representative payee who is in charge of the money.

“In Milwaukee County alone, the Walker administration has been taking between $3 million and over $4 million in survivor and disability benefits from foster children each year — and the state has been taking millions more from foster children in other jurisdictions,” he wrote.

In Los Angeles County, where 8-year-old Gabriel had lived with his family, the contract language between the county and Maximus states that the contract management services can be performed “more economically” by an independent company than county employees.

Hatcher called it a “striking” statement, arguing it seemed as though the contract had been made “because it’s going to be cheaper.”

Producers were also unable to uncover documents that showed that Maximus’ contract with the county had been worth about $110 million over the last decade, Therolf said. Although there had been a provision that required the contract to go out to competitive bidding every three years, he explained it had only gone out to bid twice in the last 14 years.

“Year after year they kind of consistently did not meet a lot of the requirements required of their contract, like the work participation rates, the way they handle case files, but what we saw was their contract kept getting extended each time,” Cecilia Lei, a graduate student researcher at UC Berkeley School of Journalism, said in the docu-series.

While the county continues to contract with the company, the series questions whether Maximus' policies are serving the best interests of those in need, highlighting Fernandez's case and how the possibility of overtime concerns may have kept those from stepping in to help. Martinez made the report only after deciding to risk his job by going against the advice of his supervisor, he said in the series.

“I would think you have to hope in that case for humanity to take more importance over the mission,” Hatcher said of the decision the workers were allegedly faced with that day. “If you, an employee for a company whose really loyal to that company, you are forcing a situation where the individual has to break that loyalty of mission in order to do what’s right.”