Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

Has The Department of Children and Family Services Changed Since Gabriel Fernandez's Death?

Bobby Cagle, the Director of Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services, claims that drastic changes have been made since Gabriel Fernandez died.

Criticism of the Department of Children and Family Services in a number of states has arisen following the deaths of several children — including the tragic death of Andrew "AJ" Freund Jr. — but the murder of Gabriel Fernandez was exceptionally shocking and the case has drawn new scrutiny due to a recent docuseries.

The 8-year-old boy from Antelope Valley, California died in 2013 after enduring months of abuse by his mother, Pearl Feranandez, and her boyfriend, Isauro Aguirre. They put out cigarettes on him, shot him in the face with a BB gun, made him eat cat litter and feces and forced him to sleep in a locked cabinet, often while gagged and bound. All the while, Gabriel would make heartbreaking drawings for his mother, expressing his unconditional love for her.

To make matters worse, the Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services, or DCFS, was alerted to the abuse, but Gabriel died nonetheless.

Four DCFS workers connected to Gabriel’s case — social workers Stefanie Rodriguez and Patricia Clement, along with supervisors Kevin Bom and Gregory Merritt — were prosecuted. All four were fired from their jobs following an internal investigation, but the criminal case against them was dropped following an appeals court ruling.

As shown in the Netflix docuseries "The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez," the Blue Ribbon Commission on Child Protection was formed in 2014 in response to Gabriel's death. They decided that the DCFS needed to make immediate changes to better serve the community. The commission's report stated: “We cannot stand idly by and wait for another child to meet the fate of Gabriel Fernandez. Sparked by his and other tragic child fatalities, community outrage, and a series of unsuccessful attempts at reforming the County’s child protection system, the Board of Supervisors agreed that action is necessary.”

They called the current state of child care in the county a “state of emergency” and outlined a road map for changes in their report.

So, what changes have actually been made?

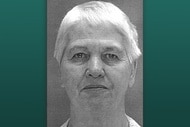

Bobby D. Cagle, who has been the Director of the Los Angeles County DCFS since 2017, told Oxygen.com that “there were already a tremendous number of reforms that were under way when I arrived that were a result of the Blue Ribbon Commission and their recommendations.”

Cagle previously worked at a Georgia DCFS following a number of high-profile deaths in that state. When Cagle got to Los Angeles County he implemented additional changes on top of the reforms recommended by the Blue Ribbon Commission, he said.

These changes include switching the way that DCFS staff is trained “so we have gone from more of a classroom lecture type format to a format that is experiential," he told Oxygen.com. He said that format ensures that workers demonstrate their skills in a simulated environment.

Case loads for workers have decreased to more manageable loads, the director told Oxygen.com. He claims that within the Investigations or Emergency Response Department of DCFS, a caseworker now manages an average of 11 cases as compared to an average of 18 back in 2013. He said that in the Ongoing Service Department, the average caseworker now has 20 cases as compared to 30 in 2013.

Caseworkers have received additional training on interviewing skills so that they can get better information from children, Cagle said. He said they've also been trained to recognize injuries, so they know "what an injury typical to the age that they are working with should look like versus an inflicted injury.”

He said DCFS has made it easier for workers to better access criminal records on adults whom they are working with. As a direct result of the Blue Ribbon Commission recommendations, he said an independent oversight body called the Office of Child Protection, which reports to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, has been created. Cagle said DCFS has also created its own team, called the Continuous Quality Improvement team, which is dedicated to reviewing cases and making recommendations. However, their findings remain internal and are not available to the public.

Cagle noted that he "was surprised" when he came on board to find there wasn't a team solely dedicated to reviewing cases.

Despite the changes Cagle has touted, Los Angeles Deputy District Attorney Jon Hatami, whose prosecution of the Gabriel Fernandez case is featured prominently in “The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez,” told Oxygen.com, "I just do not see the changes DCFS is referring to.”

Hatami told Oxygen.com that he still feels that DCFS workers are overwhelmed with caseload numbers. He said he has spoken to DCFS social workers and “most can’t even tell me what changes have been made since Gabriel was killed” noting that “some social workers even told me that they didn’t even know the Gabriel case.”

Hatami said that “children continue to be abused and even killed under the watch of DCFS.”

Other deaths

As the docuseries pointed out, two other boys in Antelope Valley died under similar circumstances following Gabriel's death. Anthony Avalos died on June 20, 2018 at age 10, allegedly after suffering abuse by his mother Heather Barron and her boyfriend, Kareem Leiva. Noah Cuatro, 4, died on July 5, 2019 after his parents Jose Maria Cuatro Jr., and Ursula Elaine Juarez allegedly tortured him for a period of four months, according to a press release from the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office.

Both Avalos and Cuatro were receiving services from DCFS prior to their deaths.

“That, in and of itself, tells me that enough is not being done,” Hatami told Oxygen.com.

Lawyer Brian Claypool, who is representing Cuatro's grandmother, pointed to Cuatro's and Avalos' deaths as "proof in my mind that DCFS just clearly disregarded any of those recommendations and that there is a pattern of practice of neglecting these lower income, especially Hispanic and African-American kids," while speaking with Oxygen.com.

Claypool alleged that DCFS fails to follow their own procedure and told Oxygen.com that Cagle's claims of change are "a bunch of garbage."

"They have the same spineless social workers, and by that I mean their mentality," he said, adding "this is a system problem that’s been going on for over a decade in this agency. You can't fix a systemic problem by having a Blue Ribbon Commission report come out."

Claypool also alleged that outsourcing was an issue with the department.

He told Oxygen.com that DCFS outsourced a counselor from Hathaway-Sycamores Child and Family Services, a nonprofit community mental health agency that provided services to Los Angeles County, to work with Gabriel. That counselor, Barbara Dixon, testified in 2017 that she thought Gabriel may have been abused one month before his death, according to testimony obtained by Oxygen.com.

Dixon testified that he had a black eye and bruises on his ankles and wrists, which he and his family attributed to a bicycle accident. She claimed she believed the family at first, but after a walk alone with Gabriel she grew suspicious of that story. Dixon alleged that a supervisor prevented her from reporting to the DCFS hotline.

Hathaway-Sycamores CEO Debbie Manners told Oxygen.com that Dixon then went on to have some involvement in the Avalos case "for a brief time for about a year and a half prior to his tragic death." Hathaway-Sycamores — but not Dixon — was also used for Cuatro's counseling. A DCFS spokesperson told Oxygen.com that they still currently use Hathaway-Sycamores as a service provider.

“The county is aware that this third party venue is engaging in violating mandated reporter laws and yet they still used Hathaway to counsel," Claypool told Oxygen.com, calling the move an "intentional disregard for the well being of these kids."

Manners contended to Oxygen.com that Dixon misspoke when she testified that she thought Gabriel was being abused — pointing out that Dixon had also testified that she didn't think Gabriel was abused.

Months after Gabriel died, Dixon testified that she believed the boy when he claimed his injuries were from a bicycle accident, according to a transcript obtained by Oxygen.com.

“I think it’s too bad that that [the supervisor allegation] is what got picked up out of her testimony because a supervisor would never tell their supervisee not to report,” Manners said. “That’s what the law states and that’s what we teach.”

Dixon is no longer employed with Hathaway-Sycamores, Manners said.

Oxygen.com’s attempts to reach Dixon were unsuccessful.

Alleged secrecy

Cagle told Oxygen.com that he can't talk about Avalos or Cuatro's case because they are ongoing investigations.

Hatami told Oxygen.com that he doesn't like DCFS' tightlipped responses to child deaths and alleged secrecy by their organization was a theme of the docuseries.

"I don't like secrets," Hatami said, theorizing that DCFS is often quiet because "they are afraid they are going to get sued and lose money."

Cagle told Oxygen.com that perceived DCFS secrecy is a concern in every community he's ever worked in.

”The nature of the work that we do by law, both state and federal law, is confidential because we want families to have the services we provide in a confidential setting so that they can feel as though they are being served without their very personal matters being shared publicly," he said.

Cagle added that the Los Angeles County DCFS has “taken some criticism for not doing an interview with the makers of the documentary” but noted that DCFS “cooperated with them fully” by providing the filmmakers information and access to DCFS ride-alongs.

Hatami remains critical and said he is going to continue to fight for children in his county.

“Our children deserve better,” Hatami told Oxygen.com. “Every time a child dies under DCFS watch, all the politicians jump up and say that they are making changes. Why does a child have to die for all of us to make changes? Why did Gabriel have to die for DCFS to make changes?”