Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

How The ‘Son Of Sam’ Terrorized NYC And The Evidence That Led To His Capture

The killings that made up the "Son of Sam" case shook gritty 1970s New York to its core. But what if, all these years later, we still don't know the whole story?

New York City in the late 1970’s was tough, seedy, rife with crime and corruption, and mired in a financial crisis. Reports of violent crimes in the city doubled and tripled, and as families deserted a New York on the brink, entire city blocks were left in disrepair, easy prey for eager arsonists.

But from the summer of 1976 to the summer to the summer of 1977 even the most diehard New Yorkers were terrorized by a common threat: a murderer who stalked the streets and avenues. Nobody knew where – or why – he’d strike next.

At first he was known as the .44 Caliber Killer, named for his weapon of choice. It was the gun he used to murder white, middle-class women with long brown hair, and women parked in cars with their boyfriends. By April of 1977, as his deadly spree continued unchecked, he invented his own moniker: Son of Sam.

By the end of his lethal junket six people were dead and 10 grievously wounded, many left to suffer with life-long injuries.

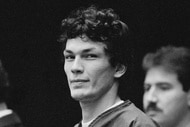

Then, another shock to the city: when the suspect was finally identified he didn't look anything like the monster they'd imagined. Instead, he was a goofy-looking postal worker from Yonkers. The 1977 arrest of David Berkowitz – the Son of Sam – sent the media into overdrive. His schlubby exterior, the narrative went, belied a sick and deranged mind. He became known internationally as the serial killer who murdered because he believed a demon-possessed dog had instructed him to. That’s the Son of Sam story most people know.

Less well known is that, after his conviction, Berkowitz admitted to his psychiatrist that the dog narrative was made up. He told reporters that he wasn’t the only gunman. He hinted at a vast conspiracy, a satanic cult of which he was just one small part. Despite these proclamations, the original narrative persisted: he was a lone wolf, a criminally insane man who killed because of dog delusions.

Journalist Maury Terry didn’t buy it. He dedicated his life to convincing the public that Berkowitz was indeed part of a larger Satanic cabal. He believed there were other shooters, including the literal “sons of Sam”: Michael and John Carr. Michael and John were the adult sons of Berkowitz's neighbor Sam Carr, owner of the infamous dog.

These theories are explored in “The Sons of Sam: A Descent Into Darkness,” a four-part Netflix docuseries that begins streaming on May 5.

Here’s a comprehensive look at Son of Sam’s notorious late ‘70s killing spree — its victims and the evidence that led to Berkowitz’s arrest — and how it turned “The City That Never Sleeps,” into a city paralyzed by fear. And why, after all these years, everything we think we know about the case could be wrong.

The Killings Begin

Donna Lauria, 18, and her friend Jody Valenti, 19, had spent the night of July 29, 1976 out dancing at a local disco. Sometime after midnight they left the club in Valenti’s two-door Oldsmobile. Valenti drove Lauria to her home in the Bronx, a six-story apartment building where she lived with her parents. The two friends pulled up outside and sat for a bit in the car, windows closed, when suddenly a husky man with curly hair approached them.

He fired a gun four times into the vehicle’s passenger window, striking Lauria in the neck and killing her. Valenti was shot in the thigh but survived. The killer used a .44 caliber Charter Arms Bulldog revolver.

“It feels like it happened yesterday,” Lauria’s mother, Rose, told PIX 11 in 2016 on the 40th anniversary of her daughter’s slaying. Rose mourns her daughter, the middle child of three, by holding a Mass for her on the anniversary of her death, and celebrating her birthday each year.

“We were neighborhood buddies,” Valenti, the survivor, told the New York Post in 2016 of her friend, who was training to be a medic when she was murdered. “We both had the same interests in health care.”

It seemed like an isolated act of random violence in a violent city, until it happened again.

Carl Denaro, 20, and Rosemary Keenan, 18, were sitting in a parked car in Flushing, Queens on Oct. 23, 1976. Suddenly, gunshots rang out. “It felt like the car exploded,” Denaro recounts in the docuseries. “All the glass had broken. There was little pieces embedded in my hands.”

He yelled for Keenan to start the car and drive away, not realizing he’d been shot in the head. He woke up in the hospital bandaged but alive. They both survived.

But in the years since, Denaro has come to question many things about that night. He wrote a book in which he supports Maury Terry’s theories about multiple shooters. In 2017, he told People, “I believe other people were involved. He [Berkowitz] had help, and I am not alone in thinking this.”

As the mystery of the shootings deepened, the gunfire continued. A little over a month later, on Nov. 27, 1976, Donna DeMasi, 16, and Joanne Lomino, 18, were walking in Floral Park, Queens when they were shot. Lomino was paralyzed from her injuries.

The next victim was 26-year-old Christine Freund. On Jan. 30, 1977, she was sitting Pontiac Firebird with her fiancé, 30-year-old John Diel, in Forest Hills, Queens. Then, in the words of the legendary tabloid journalist Jimmy Breslin, “a pudgy guy with a wool watch cap on ran up to the car and held a gun out in both hands and fired three shots through the passenger window.”

Freund died from her injuries just a few hours later.

It was at this crime scene that investigators realized the .44 caliber bullets that killed Freund were from the same revolver that was used to kill Lauria. The still-unknown gunman was dubbed the “.44 Caliber Killer” by the newspapers. A serial killer was on the loose.

Virginia Voskerichian, a 19-year-old college student, was shot outside her home in Flushing, Queens on March 8, 1977, just one block away from where Freund had been murdered. The honor student was returning home from school, and as she saw the gunman she instinctively held her text books in front of her face, the New York Post reported in 2007. But the bullet ripped through the book, striking her in the face. Bystanders found her on the sidewalk, bleeding from a fatal head wound.

The .44 Caliber Killer had struck again.

Fear gripped a city already overcome by crime: reports of rape were at an all-time high, felonies were up more than 13 percent in the city in 1976 – the highest rate on record, the New York Times reported in 1977. There were 1,622 murders in New York City in 1976, compared to 312 in 2019 and 436 in 2020. But in this city, at this moment in history, it was the .44 Caliber Killer that captured the imagination of New Yorkers. They avoided lovers' lanes, left the night time streets deserted and the disco clubs empty. The tabloids buzzed with the rumor that the killer targeted women with long dark hair. Hair salons saw an uptick in women asking for short dos or blonde hair.

Berkowitz's Disturbing Behavior

All the while, Berkowitz’s mental health was unraveling.

Berkowitz was adopted as a baby and spent his childhood in Yonkers thinking his mother had died in childbirth, a detail that the young killer blamed himself for. When he found out his adoptive parents had lied to him about his birth mother’s death, he felt abandoned and unwanted. He felt he was born a mistake.

Berkowitz served time in the military, deployed to Korea, where he experimented with cocaine and LSD. When he came back to New York he took work as a taxi driver and later, as a postal worker. His behavior began growing increasingly erratic. He spent much of his free time setting fires in the depopulated city. It's possible he set as many as 2,000, the New York Times reported in 1978.

Berkowitz punched holes in the walls of his sparsely decorated one-bedroom apartment in Yonkers. Next to the holes, he’d scribble cryptic and bizarre messages, including one that read, “Hi my name is Mr. Williams and I live in this hole.”

Berkowitz also used his time to send bizarre, anonymous letters to his neighbors and former landlords. One target of his letters was his neighbor, Sam Carr and Carr’s family. They lived in a white‐shingled house just down a hill from Berkowitz’s apartment, which was located in a 110-unit brick building. Berkowitz even scrawled “Sam Carr — My Master” near his sheetless mattress, the New York Times reported in 2007.

Sam’s daughter, Wheat Carr, told the New York Times in 1977 that Berkowitz harassed the family with letters and anonymous phone calls for months, and that the harassment coincided with many of the killings and may have grown more violent. She said her family suspected that Berkowitz threw a molotov cocktail at their home. Some of the letters regarded Sam Carr’s black Labrador Retriever, Harvey. The dog was later found shot in a Yonkers backyard but survived and would go on to become a pivotal part of the Son of Sam mythology.

Brazen Taunts

On April 17, 1977, Valentina Suriani, 18, and her boyfriend, Alexander Esau, 20, were struck by gunfire as they sat in Esau’s car in the Bronx. Three shots were fired into a side window of the car at around 3 a.m. Both were shot in the head. Suriani, who was shot once, died instantly. Esau, shot twice, died hours later.

Suriani was described as a well-liked college student. She took in stray cats and played piano. Esau, a hardworking tow-truck driver, intended to propose to her. Both were killed before he got the chance.

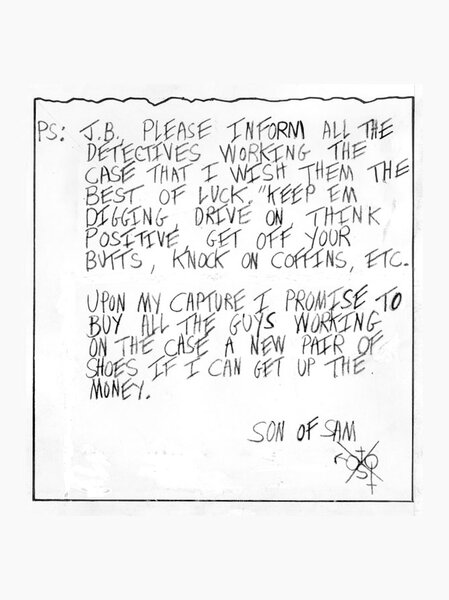

At the scene investigators found a note, addressed to Joe Borrelli, who worked homicide for the New York Police Department in Queens.

“I’m deeply hurt by you calling me a wemon [sic] hater. I am not. But I am a monster. I am the Son of Sam. When father Sam gets drunk, he gets mean. He beats his family.”

Somehow the bizarre letter got even stranger.

“I am the monster Beelzebub, the chubby behemoth,” the letter said. It ended with a taunt: “I’ll be back. I’ll back.”

It was signed, “Yours in murder, Mr. Monster.”

Berkowitz was creating his own mythology. The .44 Caliber Killer became the Son of Sam.

On May 30, 1977, Daily News columnist Jimmy Breslin received a new letter signed “Son of Sam.” The paper published the bizarre missive, prompting further panic from the public as the shooting continued.

On the night of June 26, 1977, Sal Lupo, 20 and his new girlfriend, Judy Placido, 17, were together at Elephas. Lupo asked one of the disco’s bouncers if he could borrow the keys to his Cadillac Coupe de Ville so he and Placido could have some alone time. As they sat in the car, the gunman approached. Placido was shot in the right temple, neck, and right shoulder. Lupo was hit in the forearm.

"They got into the car and were sitting in the front seat, talking and smoking cigarettes, for six to eight minutes," Detective Sgt. Edward Dahlem said, according to the Daily News. "The assailant came up on the passenger side of the car, fired one shot through the passenger window, then three more in rapid succession."

Both survived the attack.

A guest at the disco heard the shooting and the bouncer and other patrons rushed to the scene to help.

The New York Daily News reported at the time that just one week prior, an unidentified man called police in Bayside to warn them he would hit that area next.

By this point, several sketches of the shooter had been released to the public. While some looked like Berkowitz, others looked quite different, the shooter was described as tall and slim with straight hair. This would later become a key point in Terry’s theory that there was more than one shooter and a key detail in the Netflix docuseries.

On July 30, 1977, the Son of Sam attacked for the final time.

Robert Violante and Stacey Moskowitz, both 20, were parked in Violante’s brown Buick Skylark on a service road off the Belt Parkway in Brooklyn’s Bath Beach. It was the couple’s first date.

The shooter walked up to the vehicle and opened fire, shooting both of them in the head. Moskowitz was killed by a gunshot wound to the head. Violante survived but was rendered partially blind by a bullet that damaged his right eye and entered his skull. Moskowitz' mother, Neysa Moskowitz, became a visible advocate for her daughter in the press. She told the New York Post in 1999 that she was glad to learn, years later, that her daughter was held by a police officer as she died, and that she wasn't alone.

“NO ONE IS SAFE FROM SON OF SAM,” blared the front page of New York Post following the shooting.

Berkowitz Slips Up

However, this would be the last Son of Sam shooting. Berkowitz had made a few mistakes. A woman who lived nearby was walking her dog near the scene around 2:30 am and recalled passing a man who was walking strangely. Just minutes later, she heard gunshots and a car horn. She told police she had also noticed an officer ticketing a cream-colored car parked illegally near a fire hydrant, close to where Violante and Moskowitz were shot.

This was the tip that finally broke the case. Berkowitz’s car was indeed ticketed in Brooklyn on the night of the murders. When a detective looked up the ticket, they coincidentally spoke to Wheat Carr, then a dispatcher with the Yonkers Police Department. She helped direct them to her neighbor's address in Yonkers. Detectives discovered that Berkowitz’s name was among thousands given to police by tipsters. The tipster for Berkowitz? None other than Sam Carr himself; he told police he was concerned about his neighbor's erratic behavior, according to the New York Post.

The officers peered into Berkowitz’s Ford Galaxie, parked near his apartment building. Detectives could see a duffel bag in the car, with a machine gun sticking out of it. As the docuseries points out, detectives rummaged through his car without a search warrant. Then, Berkowitz headed towards the vehicle, carrying his.44 caliber revolver.

“You’ve got me!” Berkowitz said, before admitting, “You’ve got the Son of Sam.” It was Aug. 10, 1977.

Berkowitz didn’t look like a monster. Instead, “the man behind the killings was unmasked as a schlubby civil servant with a boyish face and a dopey smile,” the Associated Press reported in 2017.

After he was arrested, Berkowitz told investigators that Sam Carr’s dog was actually a 6,000-year-old demon and that this demon instructed him to kill. He also unveiled his supposed master plan, which was to carry out a mass shooting at a nightclub in the Hamptons. He told investigators that he intended to go out in a “blaze of glory” on the dance floor, armed with a semi-automatic rifle, TIME reported in 2015. He wanted to target “pretty” girls before getting shot dead by police.

In September of 1977, Berkowitz mailed the Carr family a letter from jail, referring to Sam Carr as “Sam, my Lord,” and “Papa God,” according to the New York Times. The letter, which the Carrs gave over to the police, featured plenty of vitriol against Harvey the dog. Furthermore, it threatened to expose Sam Carr as the real force behind the slayings and other unrelated murders.

But in 1978, Berkowitz pleaded guilty to six murders and various arson attacks around New York City. He was sentenced to six life sentences, one for each murder.

After his conviction, Berkowitz went back and forth on whether he'd invented the demon-dog story.

“It was all a hoax, a silly hoax,” he wrote in a 1979 letter to his psychiatrist, according to New York Magazine.

But years later he said, it was not a hoax, explaining that communicating with animals was one of his satanic tricks.

Berkowitz also claimed that the Carr brothers participated in the killings and that they pulled the trigger at several of the murders.

By this point, however, the New York Police Department didn’t seem interested in new information about the case, at least according to Maury Terry. Rather, he suspected that they, as well as New York City residents, just wanted to move on. But Terry would spend the rest of his life trying to prove that there was more to the story.

Soon, both Carr brothers would both die under suspicious circumstances, fueling Terry’s theories.

John Carr died in a North Dakota motel in 1978 of gunshot wounds, the New York Times reported.

Lt. Terry Gardner, a deputy sheriff who investigated his death, told the Times, “There is no doubt in my mind, based on interviews I conducted and information I have obtained, that John Carr and Berkowitz knew each other well.”

Michael Carr died in a solo traffic accident on Manhattan's West Side Highway in 1979, the New York Times reported that year. Terry was convinced his death was suspicious.

In the aftermath of the Son of Sam killings, the Carrs became targets of harassment. They received more than 100 threatening or obscene letters accusing them of being accomplices to the murders.

“Why did he [Berkowitz] pick my father and my family,” Wheat Carr asked the New York Times in 1977. “ It's eating us up. It's not enough to say to ourselves that he [Berkowitz] is sick.”

Terry went on to write a successful book about his theory and he made several high-profile television appearances in which he professed his beliefs about the Son of Sam killings. But in the public mind, the narrative remained the same: Berkowitz, suffering from delusions, was a lone shooter.

In 1979, one of Berkowitz's fellow inmates slashed the notorious killer's neck. He survived the attack, but the wound is still visible. In 1987, Berkowitz became an evangelical Christian and now calls himself "Son of Hope." He is still alive and serving multiple life sentences at Shawangunk Correctional Facility.

In what might be the strangest twist in this very strange case, Berkowitz has befriended several victims and people connected to the case over the years. Shayna Glassman, the daughter of Craig Glassman, one of Berkowitz's old Yonkers neighbors whom he used to terrorize, began visiting him in prison, CBS News reported in 2017. In her later years, Neysa Moskowitz forgave Berkowitz for killing her daughter. He sent her letters and even a Mother’s Day card, the New York Post reported in 2006.

[Photos: Getty Images]