How A Former Spy Solved His Own Murder And Changed The Relationship Between Two Countries

During his final weeks spent in a London hospital, former KGB agent Alexander Litvinenko told authorities he'd been poisoned with a cup of tea. When investigators finally realized what was killing Litvinenko, authorities had to follow a literal radioactive trail of evidence.

The real-life story of “Russian spy” Alexander Litvinenko is one shrouded with Hollywood-esque coverups and tensions between two of the world’s most powerful nations.

In the early morning hours of Nov. 3, 2006, the former counterintelligence agent for the Soviet Union’s KGB (later the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation [FSB]) was admitted to Barnet General Hospital in north London, according to the 2016 findings of a public inquiry led by the British High Court’s Sir Robert Owen.

Per the 329-page report reviewed by Oxygen.com, Litvinenko’s wife, Marina Litvinenko, reported her husband’s sickness was “sudden and unexpected” when symptoms appeared on the night of Nov. 1.

Marina said Litvinenko appeared “very exhausted” and could not stop vomiting. In the following days, the patient also presented bloody diarrhea and pain throughout his body. Litvinenko’s condition worsened, despite being treated for dehydration and early suspicions of food poisoning. His hair fell out, and his bone marrow degenerated, per the findings.

RELATED: Police: Russian Ex-Spy And His Daughter Poisoned In London

Eventually, he was moved to London’s University College Hospital.

Mr. and Mrs. Litvinenko — who shared one son — soon expressed their beliefs that Litvinenko was poisoned by “dangerous people,” according to the report. Acting on this theory, medical professionals began administering Prussian Blue to treat what was then suspected to be radioactive thallium poisoning, and Litvinenko reported feeling better. But soon, the symptoms violently returned, puzzling doctors who admitted they were in “uncharted territory” when test after test showed nothing conclusive. Soon, Litvinenko’s organs began shutting down, and he suffered multiple heart attacks.

On Nov. 21, one test showed a “spike” of polonium — a rare radioactive element discovered by famed physicist Marie Curie in the 1890s. However, experts said that though the symptoms fit, polonium would have been an “unlikely cause” and attributed the positive result to the plastic bottle which stored Litvinenko’s urine sample.

Further testing proved two days later, on Nov. 23, that polonium was, in fact, present in Litvinenko’s urine, mere hours before he suffered his final — and fatal — heart attack.

Furthermore, tests proved Litvinenko was poisoned by isotope Polonium-210, which, in mass, is around 250 billion times more toxic than hydrogen cyanide, according to Medical News Today. Essentially, any place that Litvinenko went or anything he touched was at risk of radioactive contamination, as was anything in the poison’s path whilst in the hands of Litvinenko’s alleged assassins.

From his deathbed, Litvinenko participated in several interviews with the Metro Police Service in an attempt to catch his killer or killers.

“I have no doubt whatsoever that this was done by the Russian Secret Services,” Litvinenko told Det. Inspector (DI) Brent Hyatt. “Having knowledge of the system, I know that the order about such a killing of a citizen of another country on its territory, especially if it [is] something to do with Great Britain, could have been given by only one person… That person is the president of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin.”

Many, including The Guardian, would refer to Litvinenko posthumously as “the man who solved his own murder.”

One day after Litvinenko’s murder, Sergey Abeltsev of the Russian State Duma (parliament) referred to the victim as a traitor whose “deserved punishment” should be viewed as a “serious warning” to those going against Russia, according to the inquiry.

Vladimir Putin himself made comments with “a verbal levity that border[ed] on the macabre,” per the report.

“The people who have [killed Litvinenko] are not God,” Putin told the media. “And Mr. Litvinenko is, unfortunately, not Lazarus.”

Before his death, Litvinenko proffered three suspects who could have poisoned him on Putin’s orders, only two of which — former Russian FSB agents Andrei Lugovoi and Dmitri Kovtun — would leave a deadly trail of polonium in their paths.

“There was an issue on the evidence as to how, and in particular, on whose initiative, the meeting… was arranged,” the report stated.

Litvinenko told authorities he’d met the pair at the Millennium Hotel’s Pine Bar on Nov. 1, where it’s believed the men spiked his tea with the poison — seemingly unaware of the potentially catastrophic potency of their alleged murder weapon.

“I swallowed several times but it was green tea with no sugar, and it was already cold, by the way,” Litvinenko told authorities, claiming Lugovoi insisted he drink. “I didn’t like it for some reason.”

Ultimately the alleged killers left a radioactive trail of evidence.

“The polonium had originated at a nuclear reactor in the Urals and a production line in the Russian town of Sarov,” the Guardian reported. “A secret FSB laboratory, the agency’s ‘research institute,’ then converted it into a dinkily portable weapon.”

More than 200 police officers, with help from scientists from the Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE) and the Health Protection Agency (HPA), had the unprecedented task of testing multiple locations for polonium radioactivity. Destinations included hotel rooms where Lugovoy and Kovtun stayed, restaurants and even a football (soccer) stadium where Lugovoi took his family to see Moscow play Arsenal on the day of Litvinenko’s poisoning.

Investigators also found the teapot — later used by other customers — used at the Pine Bar where “extremely high” levels of polonium-210 were present.

Hotel surveillance video confirmed the tea-drinking session between the men.

In total, 733 people had to be tested for polonium-210, with 716 presenting no risk of developing illness, according to a 2007 article by The Guardian. The HPA stated 17 people had elevated levels but that “any increased [health] risk in the long-term is likely to be very small.”

On May 22, 2007, police and Crown prosecutors said there was enough evidence to prosecute Andrei Lugovoi. However, Lugovoi would not face prosecution because of Russia’s stance on forbidding the extradition of their citizens to the UK (as is the case in several countries around the world, including Germany and France, following BREXIT).

Lugovoi and Kovtun denied having anything to do with Litvinenko’s death, and in 2007, Lugovoi publicly blamed UK intelligence agency MI6 for orchestrating the assassination. (Marina Litvinenko, would later testify that her husband was a paid consultant for British intelligence [either MI5 or MI6] but contended that he never worked as an agent).

Other witnesses privy to Litvinenko’s dealings said he consulted with UK agents to combat Russian organized crime, which he had done previously as a KGB/FSB agent back in Russia.

Before climbing the ranks within the KGB, Alexander Litvinenko was originally born some 300 miles south of Moscow in Voronezh. The inquiry found Litvinenko, as a child, primarily grew up in the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains, south of the former USSR near Chechnya.

At 17, he joined the military, climbing the ranks to lieutenant, and later worked in intelligence as part of the Soviet Union’s interior ministry.

In 1988, Litvinenko was enlisted in the KGB, then operating alongside Vladimir Putin, who’d worked as a foreign intelligence officer for 15 years (before becoming president in 2000). In the early 1990s, around the time of the First Chechen War, Litvinenko worked in anti-terrorism and counterintelligence.

“These were times of considerable instability in Russia,” the inquiry stated.

During this time, Litvinenko began investigating a Central Asian heroin smuggling operation and allegedly found “widespread collusion” between the criminal group and KGB officials, including Vladimir Putin.

Tensions grew when, in 1998, Litvinenko and other former FSB agents directly blamed Putin for an assassination attempt against friend and billionaire oligarch Boris Berezovsky — a man accredited for “facilitating the rise” of Putin, according to the inquiry. (Berezovsky would also have a falling out with Putin shortly after his presidential election and died under mysterious circumstances in 2013).

“As an FSB officer in the 1990s, Litvinenko had been shocked to discover how thoroughly organized crime had penetrated Russia’s security organs,” the Guardian reported. “In his view, criminal ideology had replaced communist ideology. He was the first to describe Putin’s Russia as a mafia state, in which the roles of government, organized crime, and the spy agencies had grown indistinguishable.”

Litvinenko’s accusations against Putin were enough to land him in a Russian jail for eight months, according to the inquiry, before he was acquitted of charges of abuse of power in November 1999.

RELATED: 'She’s Bad, She’s Bad, She’s Bad': House Cleaner Kidnaps And Kills Rich Scientist

In 2000, Litvinenko, along with his wife and son, sought asylum in the UK, where he later penned two books, including “Blowing Up Russia: Terror from Within,” which further accused the FSB of a series of Moscow bombings that were allegedly deployed to assist Putin’s rise to power.

“The evidence shows that Mr. Litvinenko’s political campaigning work, and in particular, his vocal criticism of President Putin, continued until his final illness,” according to the report. “There does not appear to have been any let-up — either through concern at what the new Russian laws might herald or because of his increasing security work.”

British investigators said the “climax” of Litvinenko’s claims while in exile came when he published an article on the Chechenpress website in 2006, accusing Putin of being a pedophile.

“It hardly needs saying that the allegations made by Mr. Litvinenko against President Putin in this article were of the most serious nature,” the inquest findings continued. “Could they have had any connection with his death?”

Shortly after accusing Putin of abusing young boys, Litvinenko also pointed to the president for the assassination of Novaya Gazeta Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya, who was also a close friend of Litvinenko and an outspoken critic of Putin.

On Oct. 7, 2006, Politkovskaya was gunned down in front of her Moscow apartment.

On Oct. 19, just days before Litvinenko was poisoned, he publicly blamed Putin during a speech in response to the journalist’s murder.

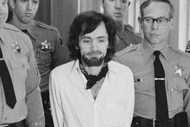

Litvinenko penned an emotional statement from his deathbed, which was released worldwide, alongside his famous hospital bed photo, after he died of radiation poisoning. He thanked hospital workers “for doing all they can” and British authorities for investigating his pending murder “with vigor and professionalism.”

He also thanked the British government for looking after him and his relatives, stating he was honored to have become a British citizen just days before being poisoned.

“You may succeed in silencing one man, but the howl of protest from around the world will reverberate, Mr. Putin, in your ears for the rest of your life,” Litvinenko wrote. “May God forgive you for what you have done, not only to me but to beloved Russia and its people.”

Following years of delays and rejections, Marina Litvinenko’s campaign to seek justice for her husband came in January 2015 with the public inquiry, according to the BBC.

The findings were published one year later.

“When Mr. Lugovoi poisoned Mr. Litvinenko (as I found that he did), it is probable that he did so under the direction of the FSB. I would add that I regard that as a strong probability,” the final report stated. “I have found that Mr. Kovtun also took part in the poisoning.”

The investigation found the hit was “probably approved” by Vladimir Putin and Russian politician Nikolai Patrushev.

Then-Prime Minister David Cameron said the ruling “confirms what we always believed,” as reported by the BBC, referring to Litvinenko’s state-sponsored murder as “absolutely appalling.”

Others, including Russian Ambassador Alexander Yakovenko in the UK, accused the British of being anti-Russian.

“We will never accept anything arrived at in secret and based on the evidence not tested in an open court of law,” Yakovenko stated.

Politicians called on Cameron to have all Russian intelligence removed from the UK, with some, including Barrister Ben Emmerson QC, calling the assassination “nuclear terrorism.”

Cameron agreed but said “some sort of relationship” must continue to exist between Russia and the UK in light of the Syria crisis. He said the union would continue with “clear eyes and a very cold heart.”

Litvinenko’s widow said she was “very pleased” with the findings.

Andrei Lugovoi and Dmitri Kovtun have never been charged.

The murder of Alexander Litvinenko continues to be a source of fascination, most recently in the upcoming UK series “Litvinenko,” starring David Tennant. The series’ rights have been sold in dozens of countries, including the United States, to AMC+ and Sundance.