Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

Who is Wayne Williams And What Is His Connection To The Atlanta Child Murders?

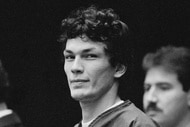

Wayne Williams, an aspiring music producer, was convicted of killing two men in Atlanta — but he's also considered the prime suspect in a string of murders of children in the late 1970s and early 1980s that terrified the community.

For more on similar cases, watch "The Real Murders Of Atlanta" airing Sunday, January 17, 2022 at 8/7c on Oxygen.

To some, Wayne Williams is a convicted murderer linked to the brutal killings of dozens of young, black children in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

But to others, Williams is an innocent man railroaded by a system eager to find a suspect and put the slayings behind the bustling city of Atlanta.

The vastly different views about the now 61-year-old and the brutal crimes that terrorized the Atlanta community are re-examined in HBO’s new five-part docuseries “Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered: The Lost Children."

The documentary coincides with Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms decision last year to re-examine the cases to determine whether there are other suspects in some of the slayings or whether the evidence more definitively links Williams to the string of murders.

According to the FBI, an estimated 29 African American children, teens and young adults were kidnapped and murdered in the Atlanta area between 1979 and 1981. Authorities plan to re-examine that list to determine whether other potential victims were initially overlooked, Mayor Bottoms said.

“We won’t be surprised if the list grows,” she said in the docuseries. “The Atlanta Police Department has already gone back to look back and forward several years at all of the murders of children in our city and the number is staggering. There were 158 murders of children and 33 are still unsolved.”

Williams — who has always maintained his innocence — was convicted in 1982 for killing two adult men, Nathaniel Carter and Jimmy Ray Payne, but investigators at the time suspected he was also responsible for dozens more deaths — including the slayings of young children.

“With the conviction of Wayne Williams we have reviewed all of the evidence that’s present today and as a result we’ve cleared 23 cases,” Lee Brown, who was serving as the Atlanta Public Safety Commissioner, said shortly after Williams’ conviction according to the HBO docuseries. “Effective one week from today, we will officially close down the task force operations. The decision that was made today was based on evidence.”

But just who is the man at the center of the investigation?

Growing Up An Only Child

Wayne Williams is the only child of Homer and Faye Williams and grew up in a middle-class neighborhood of Atlanta, where he maintained a close relationship with his parents.

“I knew them as a true Atlanta family,” Lee Whatley, a defense attorney who worked on Wayne’s appeals said in the docuseries. “Homer and Faye Williams were great people. Homer Williams was a photographer and he freelanced for the Atlanta Daily World. Faye was a school teacher for years. She taught some of the mothers of the missing murdered children.”

Journalist Clem Richardson described them as “really a good family” who took pride in their home.

“You could tell the house that they had bought was a modest house in a modest neighborhood,” he said. “Well-kept with mowed lawns, manicured hedges. They were people who kept their house very well.”

During Wayne’s trial, Homer Williams would testify that Wayne had lived with his parents in their three-bedroom house all his life until his arrest, according to a 1982 article in The Washington Post.

As a young boy, Homer bought his son an electric train set and bicycle. He also bought him a combination rifle and shot gun that the pair used on hunting trips, but Wayne “didn’t kill very much, so he gave that up,” his father testified.

Neighbor Sunshine Lewis recalled in the HBO docuseries that Wayne was more interested in CB radios and often came with his father to the Lewis’ basement to work on the radios.

“He was there with his father to learn about the radio,” she said. “Wayne didn’t want to play. Wayne wanted to learn about the radio and stuff, know what I am saying? He wasn’t really into children’s games or anything like that.”

The bright student was in the top ten percent of his class at Frederick Douglass High School, according to a 1991 profile in the Atlanta Journal Constitutional. Prison tests would later determine his IQ to be a superior 118.

The ‘Geeky’ Entrepreneur

As Wayne grew, his interest in the radio intensified and Wayne set up his own radio station in his home — scoring interviews with then-Georgia State Representative Tyrone Brooks, civil rights leader Julian Bond and politician Ralph David Abernathy III.

“We go into the radio station and sure enough he’s got all of the equipment lined up,” Brooks recalled in the docuseries, noting that he was in “awe” of the young “geeky” entrepreneur.

At night, Wayne often was out on the streets, capturing video footage of accidents and fires for local tv news stations.

“I knew Wayne Williams because he had been a freelance photographer for our tv station. That’s how he saw himself as a crime reporter,” former WSB anchor Monica Kaufman Pearson said in the docuseries.

Lou Archangeli, who worked in the Atlanta Police Department from 1974 to 2002, said police officers knew Wayne was the “man who showed up at their scene” and said he was often “part of the landscape” at crime scenes.

“You know, I know the streets of Atlanta,” Wayne told CNN in the 2015 special “Atlanta Child Murders.” “I have been around a while. Being an ex-news reporter and all, you know, nighttime is me. That’s the time I’m out most of the time.”

Wayne also considered himself a music talent scout and wanted to create a music group modeled after the Jackson Five.

“He allegedly went around to kids saying I can make you the next Michael Jackson and claimed to be a record producer and music producer,” journalist David Hilder said in “Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered: The Lost Children.”

Stuart Flemister was just a child when he joined a group Wayne created called Gemini.

“Wayne felt fun, he was like light, you know?” Flemister remembered in the five-part series. “He felt like a big brother. His jokes were kind of corny, you know. I feel like he would sometimes try to be cool and he really wasn’t cool.”

The Investigation

But Wayne would get pulled into the investigation of the missing and murdered children after he was stopped in the early morning hours one day driving across a bridge.

The bodies of the missing children were initially found in abandoned parts of the city — strangled, shot, bludgeoned or stabbed to death — but after media reports suggested that investigators had found possibly telling fibers on some of the bodies, the victims began showing up in rivers and bodies of water instead.

Investigators decided the killer may be dumping the bodies from bridges and staked out bridges throughout the city.

Around 3 a.m. on May 22, 1981 authorities heard a splash in the water off a bridge over the Chattahoochee River.

“I was really startled,” police recruit Bob Campbell said on CNN of hearing the splash. “It sounded like a body entering the water.”

Officials pulled over an almost 23-year-old Wayne Williams who had been driving over the bridge in a white station wagon.

Former FBI Agent Mike McComas, who was on the scene that night, said that Wayne told investigators that he was a talent scout and had been out in the middle of the night because he had an early morning appointment with someone named “Cheryl Johnson.”

“He said, ‘I am out here trying to find her apartment,’” McComas said in the docuseries. “That just wasn’t believable. Who goes out at 3 o’clock in the morning for an…appointment four hours later just to ensure that he’s not late. It just didn’t cut it with me.”

Authorities did not have enough reason to hold Wayne and let him go, but when Nathaniel Cater’s body washed up in the river two days later, they turned their attention back to the possible suspect.

Wayne has repeatedly denied that he ever threw anything off the bridge that night.

“There was never any incident on the bridge. I never stopped on the bridge. I never threw anything off the bridge and nobody ever testified that I did,” he said in the docuseries.

Not only had Wayne been discovered on the bridge that night, but investigators said a profile created of the killer suggested he may have a previous history of impersonating a police officer. Wayne did have a prior arrest for impersonating an officer.

He was brought in to the station for questioning and was given a lie detector test. The test indicated deception during questions directly related to whether or not he had killed Cater, according to Joseph Drolet, who served on the prosecution against Wayne.

“At that point, I knew I was a suspect, there was no question,” Wayne said. “In my stupidity and naivety I had hoped that by trying to cooperate with these people I could rationalize and explain some things and I figured sooner or later they’d leave me alone.”

But authorities did not leave Wayne alone and arrested him at his parents' house on Father’s Day in 1981.

“Everything stopped, my world, everything just stopped at that point. I can’t even describe how I felt,” Wayne said.

During the trial, much of the evidence against Wayne centered on fibers found on the victims’ bodies, including a green fiber that analysts believed matched the green carpet in the Williams’ home.

Witnesses also testified that they had seen Wayne with some of the victims prior to their deaths. Wayne’s sexuality also came into question during the trial with prosecutors alleging that he was a gay man expressing pent up rage against young black men.

“Wayne Williams was a total fraud,” Arcangeli said in the docuseries. “He had no contracts with recording studios. He didn’t sell anything. He never made any money. He was using it as a cover. He might have been trying to make money, but he failed. His failure was directed at young black men that he resented. I believe that he was a homosexual who hated young, African American men.”

But Wayne and his family continued to proclaim his innocence and believe he was being railroaded by investigators who needed to make an arrest in the high-profile case. Wayne himself pointing to the lack of physical evidence in the case.

“The bottom line is, nobody ever testified or even claimed that they saw me strike another person, choke another person, stab, beat or kill or hurt anybody, because I didn't,” Wayne told CNN in 2015.

Wayne’s defense attorney Mary Welcome said in the docuseries that in the years since Wayne’s conviction she’s been asked repeatedly whether she thinks he’s guilty.

“I have to say, he was a lot of things, and sometimes he made me — perhaps its unlady-like — but he made me pissing angry, because he was difficult. But while he was a lot of things, I never saw a killer,” she said.

It took a jury just 11 hours to convict Wayne of Carter and Payne's killings. No charges were ever filed in any of the children’s murders and officials closed 23 cases in the days that followed without any further investigation.

Later appeals also drew into question the credibility of the witnesses and the fiber evidence. The defense team also argued that other possible suspects in the children’s murders were ignored including a family involved in the Ku Klux Klan and witness who claimed a convicted felon had killed one of the victims, Clifford Jones.

Some of the parents of the child victims also continue to maintain that Wayne is innocent, including Camille Bell, who created the Committee To Stop Children’s Murders after her 9-year-old son Yusuf was strangled to death.

“I am convinced Wayne Williams is innocent,” she said in an old news clip re-aired in the docuseries. “I am convinced that this was a political, more of a political thing than it was a trial about guilt or innocence.”

Atlanta Police Chief Erika Shields said it was “shockingly negligent” for authorities to close the 23 open cases following Wayne’s conviction. She hopes the new investigation into the deaths will provide the victims' families with more answers.

“I think the pressures were so extreme that once Atlanta was provided an out, they took it,” she said.

Life In Prison

Wayne is currently serving two life terms in prison. He has said he spent his days reading spy thrillers from the prison library, watching sports on television or talking with his father — who has since died — on the phone, according to a 1991 profile of his life behind bars by the Atlanta Journal Constitution

Corrections officials described him at the time as a “good inmate.”

The Atlanta child murders and Wayne WIlliams were also depicted in the second season of "Mindhunter" in 2019.

Wayne last went before the parole board in late 2019, but his parole was denied, according to the Atlanta Journal Constitution.

Retired detective Danny Agan applauded the parole board’s decision.

“I am not surprised at all given all the facts that are known, how strong his conviction was,” he told the local paper. “It was held up under years of appeal. There’s no reason to believe the conviction was flawed. In my opinion he is still a threat to society. He’s unrepentant.”

For more on similar cases, watch "The Real Murders Of Atlanta" airing Sunday, January 17 at 8/7c on Oxygen.