Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

Why Don’t Missing Kids Appear on Milk Cartons Anymore?

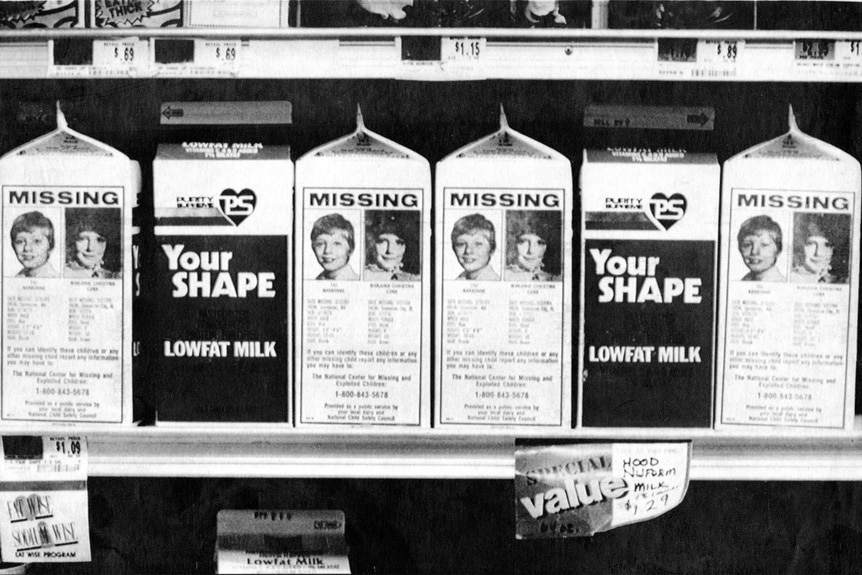

In the 1980s, images of missing children were plastered on the side of milk cartons in the hopes that families sitting down to eat breakfast together would see the photos of kids who had disappeared and be on alert in their own communities.

When a child goes missing today, word is spread through an Amber Alert or digital missing persons poster — but national efforts to increase awareness of missing kids began four decades ago with a breakfast staple.

In the 1980s, images of missing children were plastered on the side of milk cartons in the hopes that families sitting down to eat breakfast together would see the photos of kids who had disappeared and be on alert in their own communities.

While it began as a local effort in Iowa, the idea quickly caught on across the nation.

“It was, at the time, an extremely forward-leaning, cutting edge idea on, 'How do you engage the community?,” John E. Bischoff III, vice president of the Missing Children Division at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), told Oxygen.com.

The program only lasted for a few years, but according to Bischoff, it served as “one of the foundation blocks” to the digital poster distribution program that's used today by the NCMEC. And it played a vital role in increasing awareness about missing children across the nation.

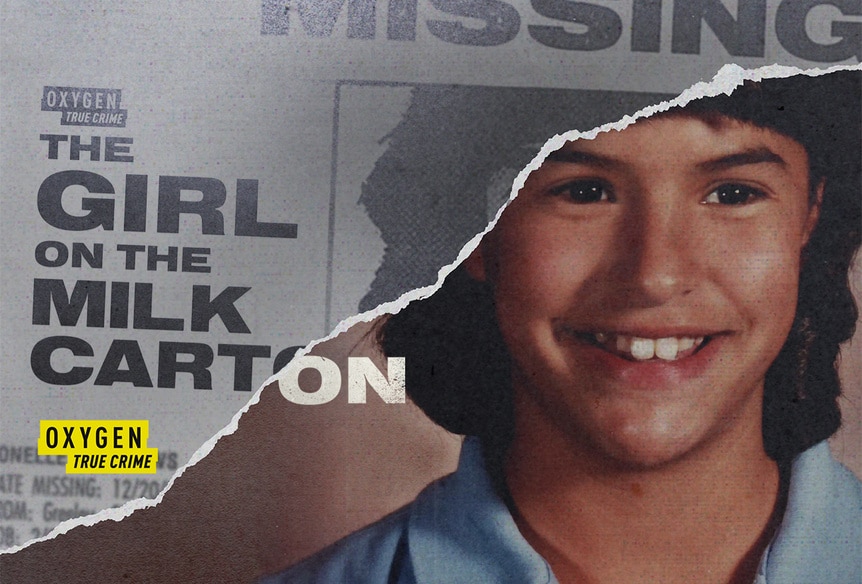

The two-part special, The Girl on the Milk Carton — debuting on Oxygen on Sunday, August 25 at 7 p.m. ET/PT. — highlights one of the first missing children to appear on the cartons, Jonelle Matthews. Here's a closer look at the Milk Carton Program, how it got its start, how effective it was, and why it ended.

How did the Milk Carton Program get its start?

The program began in September of 1984 when Anderson Erickson Dairy in Des Moines, Iowa, ran photos and short bios of two missing paperboys from the area on half-gallon milk cartons, according to The Des Moines Register. Johnny Gosch was 12 years old when he disappeared while on his Register paper route the morning of September 5, 1982. Nearly two years later, 13-year-old Eugene Martin disappeared on August 12, 1984 while he was delivering for the same newspaper.

“They were abducted, never to be seen again, and you know, they’re still missing today, unfortunately,” Bischoff told Oxygen.com.

Within months, other dairies from across the country started doing the same. In December of 1984, the National Child Safety Council launched a national version of the effort, called the Missing Children Milk Carton Program, according to the organization's website. Weeks later, the Council's site states, 700 dairies from across the nation were taking part.

At the time, the NCMEC was just getting started, but Bischoff said the center assisted in the effort by acting as a “national clearinghouse to help organize photos” and by getting the missing children pictures to the right location where they stood the greatest chance of making a difference. The organization’s 800 number was also listed on each milk carton, along with a grainy photo and brief bio of the missing child.

How effective was the Missing Children Milk Carton Program?

It’s difficult to know exactly how successful the program was because data tracking methods in the 1980s weren’t as advanced as they are today, according to Bischoff.

There were some notable successes like the case of 7-year-old Bonnie Bullock, who spotted her own photo on a milk carton while in Colorado and showed a friend who told her parents. Bullock, who had been taken by her mother during a custody dispute, was later reunited with her father, according to an Associated Press report at the time.

The NCMEC stated in a July 2024 blog post about the program that some "felt that given the large number of missing child cases that were placed on the side of milk cartons, the recovery rate was low." The post continued, "Statistically, not that many children were found as a direct result of the program. However, there are some success stories."

In addition to Bullock's case, the organization also pointed to a Lancaster teen who made it home after seeing a milk carton image.

What the program did accomplish was engaging the public in the search for missing children like they'd never been before. Decades after it was unveiled, many still remember the campaign to this day, a sign of its impact.

“It did more than it ever was intended to do,” Bischoff told Oxygen.com. “It raised awareness about missing children in the United States.”

Why did the Milk Carton Program end?

While the program was memorable, it wasn’t long lasting. Bischoff said that the effort lasted somewhere between one to two years. By the late 1980s, it was being phased out. “It stopped for a couple different reasons — one was because some people saw it as bringing sadness to the breakfast table,” Bischoff told Oxygen.com.

Others felt it was frightening for children to see the missing kids on milk cartons before heading off to school, according to the NCMEC.

Some critics felt the program fostered a “stranger danger” narrative, the NCMEC states, especially considering that abductions by people who aren't family members represent less than 1% of the missing child cases reported to the organization.

Experts now believe there are much better ways to talk to your children about the risks of kidnapping than to frighten them about strangers. Those talking points include teaching your kids not to keep secrets from parents and guardians, and telling them to always checking with a parent or adult in charge when anyone asks for help or attempts to get them to go somewhere.

The methods used today to find missing children

In the years after missing child advocates shifted away from the Milk Carton Program, the NCMEC transitioned to a paper version of a missing child poster, which could be sent to the public as part of mass mailings or hung in local businesses.

Today, many of those efforts are going digital. One major advantage, according to Bischoff, is that in the past, once a missing child was recovered, NCMEC would have to work to get the image recalled, taken down and replaced with another missing child who need help. That process is now much smoother.

“Nowadays with digital, it is nothing more than a couple of clicks in our database,” he said.

Just like in the 1980s, one of the biggest challenges remains finding ways to get the images in front of the public. NCMEC does just that by utilizing social media, cell phones and the media.

RELATED: Girl, 8, Vanishes from Her Georgia Neighborhood and 14 Hours of Search Time Are Lost

The organization also still uses some creative tactics to target the public, like partnering with gas stations to have the images appear on the screen at the gas pump while someone is pumping gas, or using large billboards along the highway that can be changed digitally.

It's also developed a QR code, which, once scanned, produces a list of all the missing children within 50 miles of a location.

“If you scan the QR code at an airport in Virginia, you’ll get children missing from around that airport within 50 miles,” Bischoff explained. “You hop on a plane, you land in California, you land in San Francisco and you scan that exact same QR code, and you’ll get children missing from within 50 miles of the San Francisco airport.”

While the strategies to alert the public about missing children may have evolved over the years, the mission remains the same: increasing the public’s awareness about children who’ve disappeared.

“We’ll use whatever tools we can to engage with the public and make them aware that we need their help and that a child is missing,” Bischoff said.