Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

Are 'Deep Fakes' The New Frontier Of Digital Crime?

So-called "deep fake" technology allows users to create videos of people performing acts that never occurred in reality. We talked with software engineer and special effects artist Owen Williams about whether we need to be scared of it.

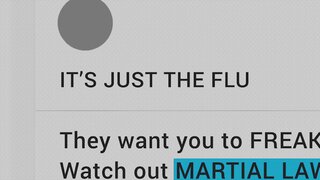

Special effects technology has seen a veritable boom in the past few decades, with CGI moving from rudimentarily crude and primitive to almost indistinguishable from reality. Now, as the creation of verisimilitudinous imagery becomes increasingly commonplace, political pundits and criminal justice experts alike are anticipating a panic around so-called "deep fake" technology, which has the potential to further complicate an ongoing international discussion about "fake news." But what, exactly, is a "deep fake" and how much of a threat will this technology pose in the future?

Deep fake (sometimes stylized as "deepfake") technology refers to synthesized and/or superimposed images and/or videos created by artificial intelligence using existing images and videos. Using machine learning, this technology could theoretically create convincing footage of a person performing an act that never actually occurred in real life.

Owen Williams, a professional software engineer and visual effects artist, offered a simple explanation.

"It's a way of using an automated software system to replace a person's face in a video with another face that is much more automatic and convincing than had been possible with past technology," Williams told Oxygen.com.

Williams noted that mainstream, popular films like "Jurassic Park" and "Blade Runner: The Final Cut" used computer software for certain scenes in ways that might have been a precursor to deep fakes: "In the film industry, this is really common. Let's say you have a character that needs to perform a stunt and you would prefer to have their face be visible. The classic workaround would be that you would only see them from the back, or their hair would be in their face so you couldn't tell it was a double. But there's a pretty involved history of filmmakers using computers to put an actor's face over a stunt double's."

"It used to be a very manual process," Williams continued. "Now, with deep fake technology, you feed a computer two things: First the video you're going to replace, and then a bunch of inputs of the face you're going to replace with. You have to get enough images of a person making different facial expressions and from different angles. You're creating a library of what this person's face can look like in different situations, and then the computer goes through and looks at the video. It doesn't need an exact match, either. It can squish and morph what it has in the library to fit what it needs. What used to require dozens of artists hundreds of hours to try and execute a really complicated effect now is only a button push."

A facet of this technology that has people worried is that a person does not necessarily need to willingly submit their face for this process to be executed, considering how many pictures exist online of most people — especially celebrities and political figures.

"There's enough pictures of any celebrity at enough angles that you can create that library [without consent]," said Williams. "There's a certain amount of work required to do that, but for any marginally popular figure that stuff is going to exist. My sense is that it's less likely that this would be as possible for a regular person."

The first deep fake videos appeared on Reddit forums in late 2017, according to Variety. A user claimed to have used his computer to create highly realistic pornographic videos of various celebrities engaged in sexual activities that never actually happened in real life. The user claimed he fed his computer thousands of photos of the stars, from which the AI could source the facial expressions and movements depicted. An app used by deep fake creators and shared on Reddit was eventually downloaded over 100,000 times. (Reddit would eventually go on to ban this kind of content, saying that it violated their policy on "involuntary pornography," according to The Verge.)

The realism this medium can achieve at the moment is doubted by Williams.

"If you ever actually watched one of these deep fakes... there's a certain amount of weirdness there," said Williams. "They're not polished. It probably will get better and better, though, especially because Hollywood has an interest in making this automated rather than paying expensive artists."

Similarly, Williams guessed that despite the panic around deep fake porn, the changing cultural attitudes around the nature of things like revenge porn or leaked nude images means that it's likely people who create this kind of media would be condemned and not be celebrated, even within the adult entertainment industry.

"It's never going to be mainstream," theorized Williams. "After 'The Fappening' thing happened on Reddit, people were able to change the conversation and say, 'This is not a scandal, it's a sex crime.' So I just don't see this becoming as much of a scandal as people think it will. People can also fairly easily find the original porn from which the deep fake was created, meaning that it's fairly easy to debunk."

But it's not just causing concern because it could be used to create fake celebrity porn. People are also worried about the political ramifications.

Political pundits began writing about the proliferation of deep fakes in 2018. A Guardian article from November of that year noted the viral spread of a video supposedly depicting President Donald Trump encouraging the nation of Belgium to withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement. This catalyzed a larger discussion about the potential for various governments to use this technology in mass disinformation campaigns, a conversation which had already been started thanks to the ongoing investigation into Russia's involvement in the 2016 United States presidential election.

The panic around deep fakes even inspired the editorial board of Bloomberg Media Group to pen a strongly worded op-ed on the matter.

"Video evidence has become a pillar of the criminal-justice system ... precisely because film seems like such a reliable record of someone’s speech or actions. Deep fakes could feasibly render such evidence suspect," they wrote in June 2018. "An overriding challenge, then, will be identifying and calling out these forgeries — if that’s possible."

Williams concurred that the nature of deep fakes threaten our notions of "reality" with regards to video evidence, but noted that this legal quagmire is not unique to our contemporary digital landscape.

"It sort of comes down to this idea that people have that video equals truth, which has never been the case. We knew this from Rodney King onwards. Or, think of Eric Garner: People thought [the officer who killed him] was innocent no matter what video of the incident predicted. To me [a lot of the fears around deep fakes] seem somewhat unfounded."

Williams listed several other incidents not involving deep fake technology that showed the ways video has been boldly manipulated to skew public opinion on a matter, like James O'Keefe's controversial takedown of ACORN and a recent scandal involving doctored video supposedly depicting CNN reporter Jim Acosta attacking a White House employee.

Williams' ultimate conclusion was that the hysteria surrounding deep fakes is somewhat overblown.

"What I see happening is, it will work both ways. If a video comes out and it's real, people will claim it's fake. If a video comes out and it's fake, people will claim it's real. Each case assumes a certain amount of truth assigned to video [itself]. It's hard to know what direction this will all go in. If The Pee Tape actually came out, for example, you know exactly what would happen: Half the people would say, 'This is bulls--t, it's some actor!' and half the people would say, 'There it is! It's real!' So nothing would really change. That tends to be what happens with new technology: Things don't change as much as people think."

[Photo: SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images]