Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

How A Former Eagle Scout Turned Into A Suburban Drug Lord Raking In Millions Each Year

Aaron Shamo made millions manufacturing fake OxyContin pills from his basement, but not all his customers would survive.

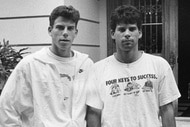

Aaron Shamo was once the clean-cut kid next door.

The Salt Lake City millennial hailed from a good family, had been an Eagle Scout and had charm and good looks.

But investigators say beneath his All-American persona, Shamo was also the kingpin of a massive criminal syndicate, recruiting others to help him manufacture deadly counterfeit opioids in the basement of his Cottonwood Heights, Utah home, according to “American Greed,” airing Wednesdays on CNBC.

Shamo sold the illicit drugs on the dark web to eager customers across the country who sought out the "Pharma Master" — as he called himself online — but, to date, authorities have identified 90 of Shamo’s customers who died from drug overdoses.

The lavish life the 26-year-old Shamo had created for himself with the proceeds would come to a screeching halt on Nov. 22, 2016. That's when federal investigators raided his property, seizing more than a $1 million in cash and drug-making paraphernalia.

“My sincere hope is that Mr. Shamo’s case is a cautionary tale for anyone whose interested in making a quick buck by selling poison, by administering death through the dark web,” Michael Gadd, special assistant U.S. attorney for the District of Utah, told “American Greed.”

Shamo began the criminal enterprise with his friend, Drew Crandall, after dropping out of college. The pair wanted to combine their interest in party drugs with Shamo’s knowledge of cryptocurrency — and began by selling Adderall on the dark web.

“It was really his ability to use and manage cryptocurrency that helped unlock the door for him to be able to set up shop and become an e-commerce pioneer, if you will, on the dark web,” said CNBC senior correspondent Ylan Mui.

The pair soon expanded to purchasing other controlled substances in bulk on the internet, including Xanax or erectile dysfunction drugs, re-packaging their purchases in smaller quantities and then selling them at a mark-up.

A few months into the operation, Shamo received a tip from a local drug dealer that the real money was in selling counterfeit OxyContin. He set out to learn how to manufacture the pills, watching YouTube videos and purchasing a pill press to set up in his basement.

Shamo also purchased a large quantity of fentanyl — a synthetic opioid up to 100 times stronger than morphine — to make the counterfeit pills.

After receiving the shipment of fentanyl, Shamo created the fake OxyContin pills by hand by using powder binders and fillers mixed with fentanyl, adding dyes, pressing the pills in the pill press and then using illegal counterfeit stamps purchased on the dark web to make the pills appear legitimate.

“These kids were trying to come up with recipes on their own,” Mui said. “They weren’t chemistry majors, they found information online and they did this through trial and error.”

While the first batch of pills they made were turned down because “they didn’t quite look like oxycodone,” Mui said eventually “they got the formula down” and their pills “became incredibly popular.”

As the popularity of their product grew, so did their sales.

“If each pill goes for, say, roughly between $20 and $40 and you are able to produce 7,000 to 10,000 pills an hour and you’re churning out pills all day, you do the math,” Brian Besser, a deputy assistant administrator with the DEA, told “American Greed.” “You end up coming up with millions of dollars in illegal drug proceeds.”

With the success of his new-found business only growing, Shamo began to take on other full-time employees who helped package and ship the goods across the United States while he reaped the profits.

At the end of his first year in business, he made nearly $3 million, according to “American Greed.”

With plenty of cash at his disposal, Shamo purchased a BMW, took lavish vacations and spent weekends in Las Vegas with his buddies.

“He had a heavy gambling addiction. He loved travel, he loved fine wines, he loved cruises, going to the beach. He spent money right and left as fast as he could get it,” Gadd said.

But while Shamo was living a life of luxury, some of his clients were dying.

Gavin Keblish, a 23-year-old counselor for children in foster care, turned to Pharma Masters to purchase 20 opioid pills to help manage chronic pain after he suffered a severe and debilitating motor cross injury.

Keblish received the package just days later and headed to a beach party with friends in Montauk, New York. Investigators believe that, at some point that night, Keblish took one of the pills. He was found dead of a fentanyl overdose the next morning in a grassy area off a roadway.

His mother, Tova Keblish, still remembers the moment she learned that her only child was gone.

“I’ll no longer have grandchildren. I’ll no longer have our own wedding for our son. That’s rough,” she told “American Greed.”

Shamo — who at this point was running his illegal enterprise on his own — also began selling counterfeit OxyContin in bulk to local drug dealers to increase his profits.

But in July of 2016, a K-9 at a U.S. Customs facility signaled on a package from the Guangdong Province in China being sent to a suburb of Salt Lake City, Utah. Authorities identified the contents inside as fentanyl — then a relatively unknown substance — and alerted federal authorities in Utah, who began their own investigation.

The package had been addressed to Sean Gygi. According to Besser, Gygi — who was 26 at the time — had a “very unassuming” background.

“(He) didn’t fit the typical profile people view as a drug trafficker or drug dealer,” Besser said.

Investigators began to surveil him and eventually decided to question Gygi about the package.

Gygi told investigators that he received the packages for his friend, Aaron Shamo — and admitted working full-time for Shamo as part of his drug-trafficking operation.

Gygi agreed to cooperate with authorities by wearing a wire and was able to capture a conversation between the pair about the business operations and Shamo’s plans to expand to the Colorado market in the future.

Gygi also picked up 79 packages from Shamo’s doorstep that he was supposed to mail to waiting customers but, rather than shipping the packages, he took them to a local police station.

“As they opened these boxes, they found, you know, 10,000 fentanyl pills in a box, 20,000 pills in a box,” Gadd said.

Besser called it “nothing like he had ever seen.”

“Mr. Shamo’s enterprise was one of the first large-scale, dark web store fronts that we had dealt with,” he said, adding that investigators were able to identify 8,000 package recipients across the United States.

When investigators raided Shamo's house just two days before Thanksgiving in 2016, they recovered $1.2 million in cash hidden away in a drawer.

Another $429,000 was hidden at his parent’s home and investigators found 500 Bitcoin linked to his cryptocurrency account, which at the time was worth a couple thousand dollars. The government would eventually sell the Bitcoin for $5 million.

Shamo was arrested on 13 drug counts, including leading a continuing criminal enterprise — which carried a mandatory life sentence — and aiding and abetting the distribution of fentanyl resulting in the death of one of his customers, Ruslan Klyuev.

Eight of his alleged co-conspirators were also arrested; all agreed to cooperate with the government in its case against Shamo.

In August of 2019, Shamo was convicted on 12 of the charges against him. The jury was unable to reach a verdict on the charge related to Klyuev’s death, but Shamo still faced a mandatory life sentence behind bars.

“I’m deeply sorry and regret the decision that I made,” Shamo said during his 2020 sentencing hearing. “I made a fool of myself and brought embarrassment to my family that I will never be able to wash away.”

To learn more about Shamo’s meteoric rise and fall, tune in to “American Greed” at 11 p.m. ET Wednesday on CNBC.